The language of mathematics is distinct from natural languages in that it aims to communicate abstract, logical ideas with precision and unambiguity. As a result, it is equipped with a system of specialized symbols and vocabularies — each with its own level of generality and formality.

Among these, there’s a particular subset of terms that is uniquely foundational and appropriate to our pursuit: the higher mathematical jargon. Loosely speaking, these are a set of specialized terms that fall into most — if not all — of the following categories:

- Specific to higher mathematics

- English-looking (with a near-technical meaning)

- Frequently-occurring

- Cross-disciplinary (i.e., not field-specific)

In brief, these are terms that are generally accessible to most, yet still provide us with a glimpse of the world of non-miniaturized mathematics — and the way their practitioners act and think. In fact, in what follows, we’ve compiled a list of 106 such terms — along with some in-depth exploration of their definitions, examples, relevance and implications.

So if you’re ready to dive into this fascinating world that is known as mathematics, then let’s get started!

(and if you’re looking for a concise rendition of all the 106 terms featured in this glossary, then you might find the following higher math jargon mindmap both interesting and useful.)

Higher Mathematical Jargon — The Definitive List (106 Terms)

A — E

E — M

- Elementary Proof

- Equivalent Claim

- Essentially Unique

- Eventually

- Exceptional Object

- Existence

- Finite

- Folklore

- Frequently

- Generalization

- Global

- Hand-waving

- Heuristics

- Identity

- If and Only If

- Indeterminate

- Inequality

- Infinite

- In General

- Intuition

- Invariance

- Lemma

- Local

- Mapping

- Mathematical Fallacy

- Mathematical Machinery

- Mathematical Maturity

M — Q

- Mathematical Representation

- Mathematical Structure

- Modulo

- Natural

- Necessity

- Null

- One-to-One

- One-to-One Correspondence

- Onto

- Operation

- Paradox

- Pathological

- Proof by Brute Force

- Proof by Contradiction

- Proof by Example

- Proof by Induction

- Proof by Infinite Descent

- Proof by Intimidation

- Proof from First Principles

- Proper

- Proposition

- Pseudomathematics

- Q.E.A.

Abstraction

The process of extracting the underlying structures, patterns, or properties of some mathematical objects, with the intention of generalizing these findings to a broader class of objects. These include, for example:

- Finding the shared properties of similar polynomials

- Formalizing the general pattern of a sequence

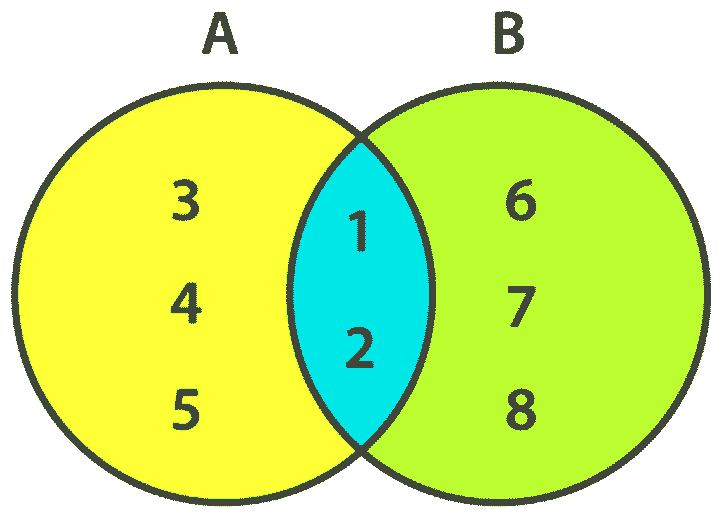

- Establishing a one-to-one correspondence between two sets

- Constructing an alternate axiomatic system for Euclidean geometry

At first, abstraction can seem a bit unappealing due to its higher cognitive demand and lack of connection to real-world phenomena. However, it can often turn out to be an integral force in bringing about a broaden applicability to a field — along with some unification in between the fields.

Did You Know?

Abstract Nonsense

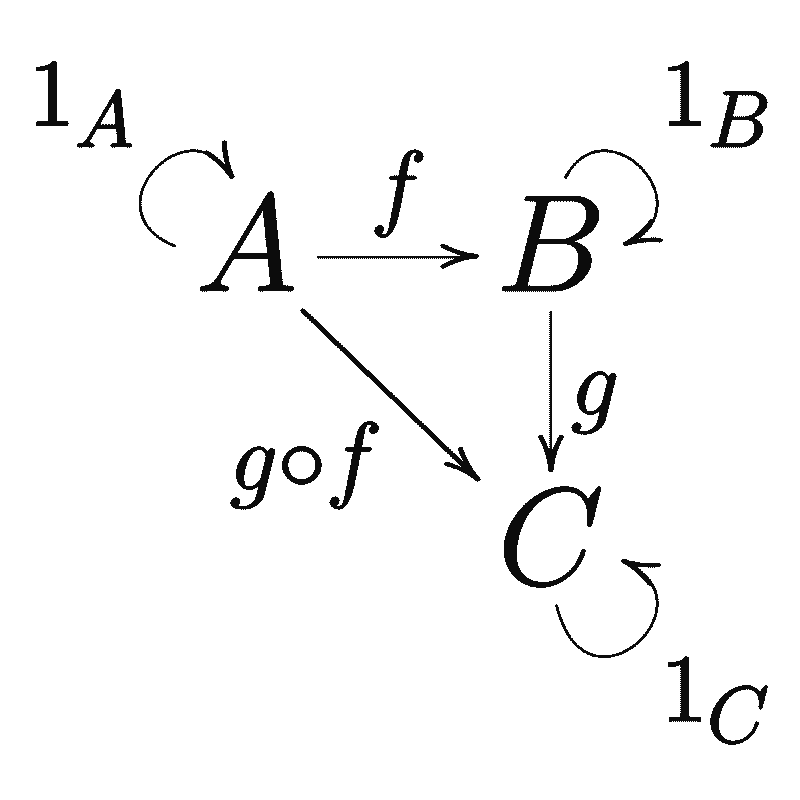

A colloquial term for category theory (a mathematical subject dedicated to the notion of category and the formalization of mathematical structures), or the methods and arguments that are related to it.

Since different branches of mathematics deal with different mathematical structures satisfying the definition of a category, category theory can be regarded as a unifying theory of mathematics — whose results are applicable to a wide range of disciplines.

In particular, if a proposition follows from abstract nonsense, then it means that its argument has more to do with the underlying categorical structure of its objects — rather than the field where it’s found. And since such arguments are often highly abstract and long-winded by nature, they are also alternatively referred to as “general abstract nonsense” or “generalized abstract nonsense“.

Abuse of notation

The act of inadvertently or deliberately using notations in a way that’s not entirely syntactically correct — but which simplifies the exposition and makes the passage easier to understand. For example, one might say that:

- “$\mathbb{R}$ is distributive” — rather than “$(\mathbb{R}, +, \times)$ is distributive.”

- “$3$ is differentiable” — rather than “the function defined by the rule $x \mapsto 3$ for all real $x$, is differentiable.”

- “$a+b+c = c+b+a$” — rather than “$(a+b) + c = (c+b) + a$”.

In the cases where the context and the assumptions are made clear and well understood, abuses of notation are usually harmless (if not actually desirable). In other cases, however, the same might not be true, and can amount to a misuse of notation — which is a faux-pas in mathematics (such as the case of $\frac{\mathrm{d}y}{\mathrm{d}x}=\frac{y}{x}$).

Algorithm

A finite series of well-defined, computer-implementable instructions to solve a specific set of computable problems. It takes a finite amount of initial input(s), processes them unambiguously at each operation, before returning its outputs within a finite amount of time. Some examples of algorithm in mathematics include:

- The Euclidean algorithm (for finding the greatest common factor of two natural numbers)

- The long division algorithm (and its variants)

- The simplex algorithm (for finding the optimal solution under a set of linear constraints)

In essence, algorithms are created to streamline the solution-finding process for a specific set of problems, though it can also remove the necessity of thinking and understanding in the process. For a a series of instructions that are quasi-algorithmic and broader in nature, the term “general procedure” is sometimes used (which, like an algorithm, could also involve some element of heuristics or recursion).

Almost

A handy adverb similar to its usage in English, but can take on specific meanings depending on the context. For example:

- “Almost all elements in a set” usually means “all but a finite/countable amount of negligible elements in the set.”

- “Almost no integer” usually means “only a finite subset of integers.”

- “A property holds almost everywhere (in a measure space)” usually means “everywhere in a set except a subset of measure zero.”

- “An event occurs almost surely” usually means that “the event has a probability of 1, even though it does not include all of the possible outcomes.”

- “An event occurs almost never” usually means that “the event has a probability of 0, even though it does contain some of the possible outcomes.”

Here, notice that “almost” doesn’t necessarily mean that the exceptional cases are “small”, and hence one is perfectly well-justified in making claims such as “almost all real numbers are transcendental” — or that “the dart almost never lands on the circumference of the board.”

Ansatz

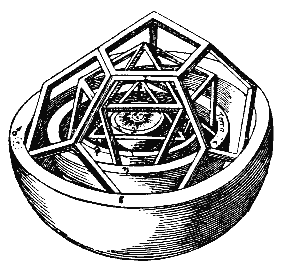

A term of German origin meaning “initial placement of a tool at a work piece” (Wikipedia), and is used in mathematics to refer to the initial, additional mathematical assumptions made to kick start the problem solving process — but which are later confirmed to be parts of the actual solution as well. Some examples of ansatz in mathematics include:

- The adoption of linear regression model to fit the data points (i.e., linear ansatz)

- The assumption that the solutions to a differential/recurrent equation take an exponential form (exponential ansatz)

- The assumption that the solution to a system of linear equations is expressible in terms of a particular vector (ansatz of particular solution).

Metaphorically speaking, the use of ansatz can be liken to drawing a picture by first establishing a framework, in that if it succeeds, then the framework can be reused as an ansatz later on, but if it doesn’t, then it’s usually discarded and marked as an instance of failure.

Arbitrarily

An adverb attached to a mathematical adjective X to make clear that something is “X with little limitation or restraint.” For example:

- An arbitrarily large function is a function capable of assuming values larger than any fixed choice of real number — regardless of the size of the latter.

- An arbitrarily small positive sequence is a sequence capable of assuming values smaller than any fixed choice of positive real number — regardless of the “tininess” of the latter.

- An arbitrarily long progression is a progression whose number of members can be made to exceed than any choice of natural number — regardless the size of the latter.

In general, “arbitrarily” is a foundational term in number theory and mathematical analysis, and can also occur in other topics where some form of degree and ordering are involved (e.g., polynomial ring).

Caution

Don’t make the mistake in assuming that “arbitrarily” means “infinitely”! If anything, “arbitrarily” usually carries a sense of being “without bound within the finite realm.”

Arbitrary

An adjective used to refer to a choice made without any specific criterion or restraint (e.g., arbitrary integer, arbitrary division of a set, arbitrary permutation of a sequence). It corresponds to the term “any” and the logical quantifier $\forall$, and hints at an element of generality in the phrase where it’s found (e.g., statement $P$ holds for an arbitrary $n \in \mathbb{N}$).

Arbitrary vs. Random

While “random” and “arbitrary” are often used interchangeably in informal discourses, in mathematics, “random” — unlike “arbitrary” — usually presupposes that the outcomes follow a probability distribution, and as such might have predictable probabilities even if the outcomes are subject to chance and unpredictability.

Axiom

Axioms, also known as postulates, are mathematical premises which are assumed to be true and along with definitions, form the foundation of a mathematical theory.

In general, axioms can be divided into two types: logical and non-logical. The logical axioms are the ones pertaining to the logical part of mathematics (e.g., $[A\rightarrow (B \wedge -B)] \rightarrow -A\,$), while the non-logical axioms are the ones pertaining to the nature of the theory itself (which might or might not be self-evident by nature).

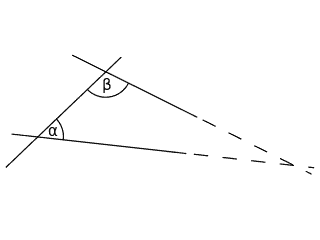

For example, the parallel postulate — which stands as the most well-known (non-logical) axiom among the five in Euclidean geometry — states that:

“If a line segment intersects two straight lines forming two interior angles on the same side that sum to less than two right angles, then the two lines, if extended indefinitely, meet on that side on which the angles sum to less than two right angles.”

And just as one can start with a set of axioms and work forward towards its consequences (i.e., a major component of theorisation), one can also take a body of knowledge and work backward towards its axioms (a process known as axiomatization).

In most likelihood, a body of knowledge is framed in terms of multiple axioms (i.e., an axiomatic system) — instead of a single axiom. In which case, extra care should be taken to ensure that the system is consistent (i.e., does not produce contradiction). Some famous axiomatic systems in mathematics include, among others:

- The Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms of set theory

- The Peano axioms of arithmetic

- The Kolmogorov axioms of probability

Beauty

A highly subjective concept corresponding to the aesthetic response to the purity, abstractness, simplicity, depth, or the orderliness of mathematics. For example, one of the equations most commonly regarded as beautiful is the Euler’s identity, which states that:

$\displaystyle e^{i\pi}+1=0 $

Since aesthetic perception of mathematics varies across individuals, other terms — such as “elegant“, “enlightening”, “exhilarating” or “interesting” — have also been used. However, it has also been argued that what’s elegant or interesting is often different from what’s beautiful in mathematics, and that beauty pertains more to the content — rather than the presentation of it.

By Inspection

A fancy way of saying “just by looking“, or that “the result can be obtained with a minimal amount of derivations, computations or background.” For example, one might say that:

“By inspection, the function $ f(x)=x^2+2x+1$ has a zero at $x=-1$.”

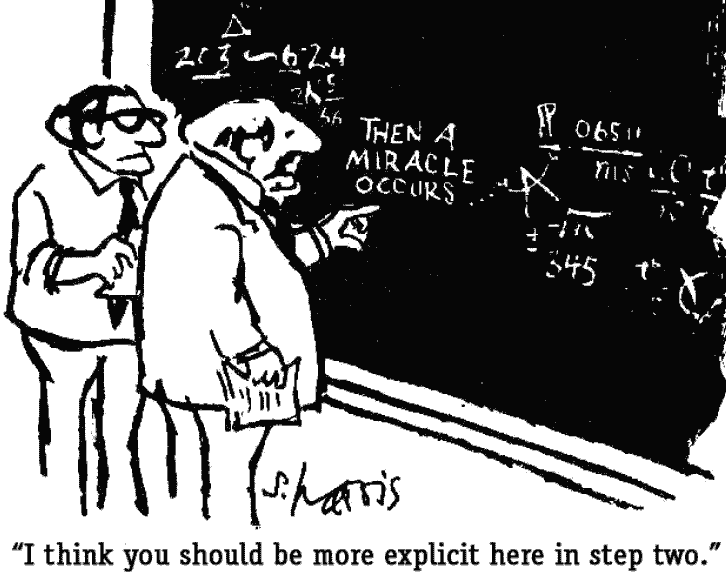

In lectures and educational texts, phrases such as “by inspection” or “it can be easily shown that” are often used as a way of simplifying the presentation of the subject matter — as well as a way of inviting others to verify their work (some of which might very well involve some tedious computations).

Canonical

An adjective derived from the root “canon”, which means standard convention or exemplar representative. However, when attached to a noun, it can take on a slightly different meaning. For example:

- A canonical proof is one that has been accepted as the standard, conventional proof (e.g., Euclid’s proof for the infinitude of primes).

- A canonical definition is one that is considered the most natural for adoption purposes (e.g., an even number as a number divisible by 2).

- A canonical map is one which arises naturally from the definition of objects, and which tends to be the one that’s the most structurally-preserving (i.e., the natural homomorphism from a group to its induced quotient group).

- A canonical form is one which has been regarded as the simplest representation of an object, and which allows the object to be identified in a unique way (e.g., $[0]$ as the set of integers with remainder 0 — when divided by some natural number).

Chaos

States of apparently-random disorders and irregularities governed by simple laws and initial conditions. Contrary to its popular usage, a chaotic behavior is deterministic and sensitive to its initial inputs — in the sense that tiny changes to the initial conditions can lead to widely diverging outcomes (e.g., butterfly effect).

More generally, the mathematical study of chaotic systems is known as the chaos theory — an interdisciplinary field which combines the theory of dynamic systems with a wide range of applications in the real world (e.g., weather forecast, road traffic, financial market, electrical circuit).

Characterisation

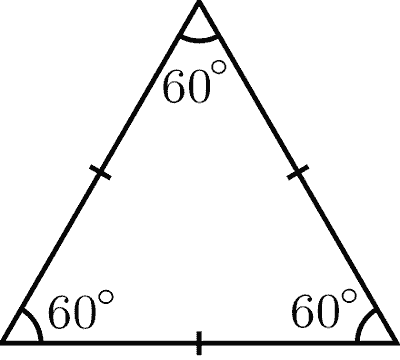

A set of conditions which uniquely defines a mathematical object, in the sense that it is logically equivalent to — but distinct from — the definition of the object. In which case, the object is said to be “characterised” by those conditions. For example:

- An equilateral triangle is defined as a triangle with three equal sides. but it can also be characterised as a triangle formed by doubling some 30-60-90 triangle in a certain way.

- An invertible square matrix is defined as a square matrix with an inverse, though it can also be characterised as a matrix with a non-zero determinant.

- The natural exponential function is often defined as the exponential function with base $e$, though it can also be characterised as the function with the assignment $\displaystyle x \mapsto \lim_{n \to \infty} \left( 1+\frac{x}{n} \right)^n$.

In general, a characterisation tends to provide additional insight into the nature of the object itself, and might even be used as an alternate definition of the object if one chooses to.

Characterisation vs. Equivalent Claim

While characterisations are a special case of equivalent claims, not all equivalent claims are characterisations — since the former needs not to be concerned with the definition of any mathematical object.

Chasing

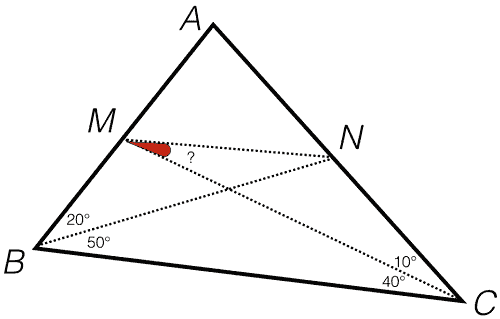

A term used in conjunction with other words to refer to the process of finishing a proof or solving a math problem — by jumping from one part to another in a logical and sequential manner. For example:

- When one attempts to solve a geometry problem by going from one angle to another, one is said to be angle chasing.

- When one attempts to prove a claim involving objects with multiple indices by going from one index to another, one is said to be index chasing (or engaging in an index battle).

- When one attempts to prove a set-theoretic claim by going from a statement about elements to another, one is said to be element chasing.

- When one attempts to prove a property of some morphisms by tracing the elements in a commutative diagram, one is said to be diagram chasing.

More generally, the term “chasing” can also be applied to other commonly-occurring objects such as equations and integrals — though such usages tend to be less common within the mathematical community.

Compact

The quality of a set or a space to be closed and bounded (e.g., closed interval, rectangles) — or other generalizations of it (e.g., the open cover definition of compactness).

In general, compactness is a key concept in topology, analysis and algebraic geometry, as many properties in these fields are often identified to be equivalent to it — or as a result of it (e.g., Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem, extreme-value theorem, Heine-Borel Theorem).

Conjecture

A notably important mathematical statement which is suspected to be true, but whose proof or disproof is still pending (even if the supporting evidence might be overwhelming). Some of the most famous conjectures of the 21st century include:

✖ Currently Unsolved Conjectures

✔ Recently Solved Conjectures

Historically, a conjecture can be resolved in three ways: if proved, it usually becomes a theorem. If disproved, it automatically becomes a false conjecture. In the case where the conjecture is shown to be neither provable nor refutable from the axioms (as in the case with the continuum hypothesis and the parallel postulate), one might choose to adopt it (or the negation of it) as an additional axiom to the system — and work from there.

Conjecture vs. Hypothesis

When a conjecture is frequently used as an assumption to build upon new mathematical work, it is sometimes referred to as a hypothesis (i.e., a better-grounded conjecture). However, a hypothesis can still be subsequently proved wrong, in which case the works built upon it would fall apart.

Constructive Proof

A proof of an existential claim (i.e., a claim of the form “there exists…”) which derives its validity by directly constructing the object being specified in the claim. This is to be contrasted from a non-constructive proof — which proves the same claim without ever constructing the said object.

For example, the statement “there is a prime number exceeding 1,000,000,000,000,000” can be proved both constructively and non-constructively — in the following ways:

- If the claim is proved by exhibiting a number that is both prime and greater than 1,000,000,000,000,000, then the proof is said to be constructive.

- If the claim is proved by demonstrating that the opposite cannot occur (e.g., proof by contradiction), then the proof is said to be non-constructive.

In general, constructive and non-constructive proofs are both valid ways of establishing an existential claim, though the latter approach could on occasion be taken as a sign of unresourcefulness, and is indeed an approach rejected by the constructivists — who choose to interpret the existential quantifier in a slightly stricter manner.

Contrapositive

Given an implication of the form $P \rightarrow Q$, the statement $\neg Q \rightarrow \neg P$ is known as its contrapositive, and is logically equivalent to the implication itself. For example:

- The contrapositive of “if $f(x)\ge 2$, then $f(x)^2\ge 4$” is “if $f(x)^2< 4$, then $f(x)< 2$.”

- The contrapositive of “all composite integers are odd” is “all even integers are prime.”

Since an implication is logically equivalent to its contrapositive, this often leads one to prove a statement by proving its contrapositive instead. In fact, this approach — also known as proof by contraposition — is especially useful when the truth of the contrapositive is easier to establish than that of the implication itself (such as the proof of “if $n^2$ is odd, then $n$ is odd”).

Converse

Given an implication of the form $P \rightarrow Q$, the statement $Q \rightarrow P$ is known as its converse. For example:

- The converse of “if $f(x)\ge 2$, then $f(x)^2\ge 4$” is “$f(x)^2\ge 4$, then $f(x)\ge 2$.”

- The converse of “all composite integers are odd” is “all odd integers are composite.”

Unlike the case with contrapositive, the truth of the converse is generally independent from that of the implication itself, even though both are often considered in conjunction with each other — for the simple reason that if one were to convey sufficiency, then the other would convey necessity and vice versa.

Inverse vs. Converse

Another variant of an implication of the form $P \rightarrow Q$ is its inverse — which refers to the statement $\neg P \rightarrow \neg Q$. While generally logically independent from its original implication, an inverse can be actually shown to be equivalent to the converse — even if their content might appear to differ.

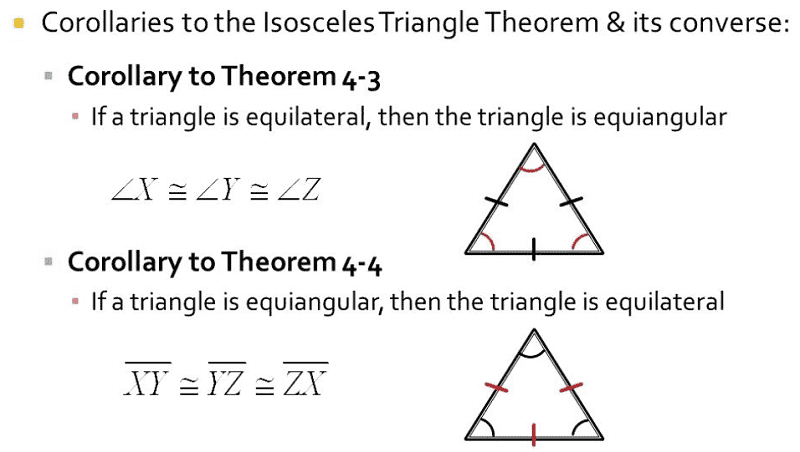

Corollary

A statement whose validity can be readily deduced from a previous, more notable statement, but whose importance tends to be secondary in nature. For example:

- The statement “$|x-y|\le|x|+|y|$” can be thought of as a corollary of the triangle inequality.

- The statement “a cubic polynomial has at least one real root” can be thought of as a corollary of the fundamental theorem of algebra (and the fact that complex roots occur in conjugate pairs).

In general, a corollary is similar to a lemma in that both tend to be of secondary importance, and is distinct in that unlike a lemma, it tends to focus on being a consequence of a result — rather than being a stepping stone towards a result.

Counterexample

An example which disproves a universal claim (i.e., a claim of the form “for all…”). For example, the claim “$2^{p}-1$ is prime for all prime numbers $p$” is false, because when $p=11$, we have that:

$2^p-1 = 2^{11}-1 = 2047 = 23 \times 89$

In this case, since $p=11$ is also the smallest example which falsifies the claim, it is also referred to as the minimal counterexample to the claim. More generally, a disproof using minimal counterexample is preferred for its simplicity and informativeness — as it might provide one with better insight on how to modify the condition of the statement so as to rule out the exceptional cases.

Deep Result

A deep result — or a deep theorem — is a mathematical statement whose proofs require a fundamentally new way of thinking, or a set of methods and techniques that are far beyond the concepts needed to formulate the claim. It frequently draws upon mathematical machinery that is atypical to the field, and is usually one for which no elementary proof is known. For example:

- The irrationality of $\mathbf{\pi}$ is known to be a deep result, since its proof requires a significant amount of development in real analysis, and cannot be tackled by simply appealing to the definition of $\pi$ or irrationality alone.

- The fundamental theorem of algebra is often considered to be a deep result, since even if it can be proved in multiple ways, each of its proofs invariably relies on the analytic completeness of real number — a concept which is non-algebraic by nature.

In some occasions, a deep result can also carry with it a connotation of being groundbreaking or influential. For example, Field medalist and mathematician Timothy Gowers defines a deep result as follows:

“A result is deep if it depends on a breakthrough idea that depends on a breakthrough idea that depends on a breakthrough idea that depends on a breakthrough idea that depends on a breakthrough idea that…”

Definition

A condition which unambiguously qualifies what a mathematical term is and what it is not, and can pertain to both a mathematical object (e.g., mesh) or its property (e.g., boundedness of a set).

Unlike the case in English, mathematical definitions must be well-defined, since they — along with axioms — form the basis of an axiomatic system, and thus can play a vital role in the process of successful theorisation as well.

Definition vs. Characterisation

By definition, a characterisation is always different from a definition, even though several characterisations might exist for the same definition. However, if a characterisation were to be adopted as the new definition, then the old definition would automatically become a characterisation as well.

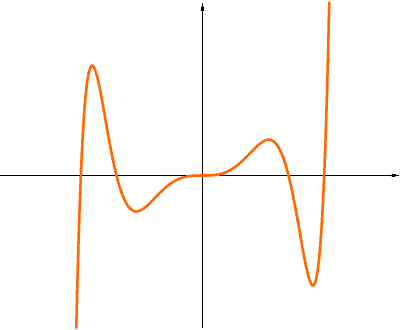

Degenerate Case

A limiting case of a class of objects (e.g., one with the smallest parameters) which appears to be notably simpler than a typical object of the same class. For example, in geometry, one can say that:

- A point is a degenerate case of a circle (i.e., as the radius approaches 0).

- A line is a degenerate case of a parabola (i.e., as the leading coefficient approaches 0).

- A circle is a degenerate case of an ellipse (i.e. as the eccentricity approaches 0).

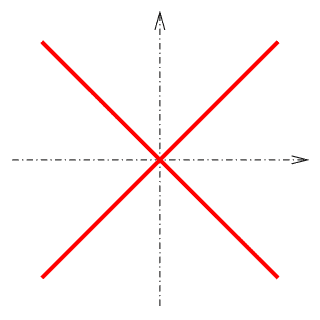

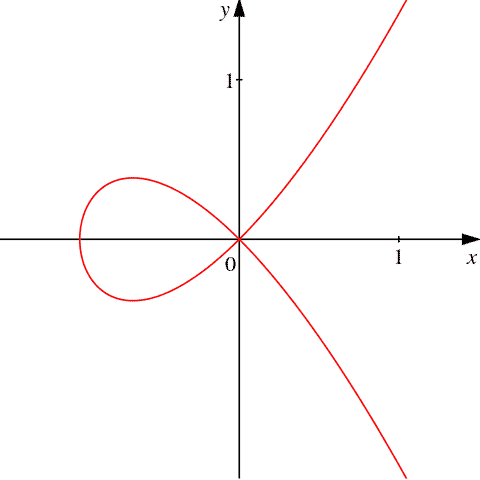

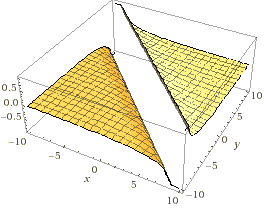

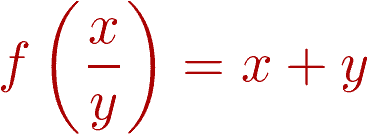

For a more elaborated example, notice that when a hyperbola of the form $x^2 – y^2 = a^2$ is altered so that the right-hand side approaches 0, it degenerates into a pair of diagonal lines — as illustrated in the graph on the right:

In general, degenerate cases are often of interest due to their notable simplicity and qualitative difference from the other objects of the same class, though results pertaining to them are not necessarily generalizable, and they might even require a different set of numerical/analytical treatments on their own.

Discovery

The act of identifying a previously-unidentified mathematical pattern, or establishing the validity or the invalidity of a mathematical claim. This presupposes the existence of a mathematical reality, which is well-articulated by, say, G.H. Hardy in his A Mathematician’s Apology:

“I believe that mathematical reality lies outside us, that our function is to discover or observe it, and that the theorems which we prove, and which we describe grandiloquently as our ‘creations‘, are simply the notes of our observations.”

Under this viewpoint, mathematics can be thought of as an endeavour encompassing both discovery and creation, in that even if mathematical truths and patterns exist independent of our actions and choices, we are still free to conceptualize them using whichever concepts and statements we can come up with.

Downstair

A metaphor used to refer to a bottom component of a mathematical expression (e.g., denominator, lower index, bottom number of a binomial coefficient). It is the opposite of upstair, and can be handy when used as an adverb (e.g., moving the $x^{-2}$ term in $\frac{x^{-2}}{y^3}$ downstair).

Elegance

A highly subjective term similar to beauty, but which is usually reserved for solutions to a problem (e.g., proofs, theories) and can take on one of the following meanings:

- Simple, unusually concise or which requires minimal assumptions and computations

- Unconventional, intuitive, insightful or unifying

- One which outlines an approach that is highly generalizable

According to Gian-Carlo Rota, a founding father of modern combinatorics, elegance is different from beauty in that elegance pertains to the presentation of the content, while beauty pertains directly to the content itself. In fact, in his The Phenomenology of Mathematical Beauty (1977), Rota stated that:

“There is a difference between mathematical beauty and mathematical elegance. Although one cannot strive for mathematical beauty, one can achieve elegance in the presentation of mathematics.”

“In preparing to deliver a mathematics lecture, mathematicians often choose to stress elegance and succeed in recasting the material in a fashion that everyone will agree is elegant. Mathematical elegance has to do with the presentation of mathematics, and only tangentially does it relate to its content.”

Whichever the interpretation, elegance remains one of the holy grails of mathematics, and is reflected in the way one tackles a problem incessantly, until a path of least resistance — such as one that involves a minimal amount of deep results and mathematical machinery — is found. As such, elegance is often a reflection of a deep understanding of the subject matter.

In contrast, certain approaches — such as those that involve laborious calculations and breaking a proof into a dozen or more cases — can be regarded as clumsy and awkward, as it might reflect a lack of understanding or mathematical maturity.

Elementary Proof

A proof of a claim which — while not necessarily a proof from first principles — only involves basic notions and methods within the field without much development into the subject matter. For example:

- In linear algebra, the standard proof for the associativity of matrix multiplication is generally considered to be elementary — since it does not require much beyond some definitions and some borderline-tedious computations with summations.

- In real analysis, the standard proof of the intermediate value theorem (i.e., one which relies on the completeness of real numbers) can be also regarded as elementary, since even if the approach is clever, it ultimately does not require extensive development into real analysis — or tapping into the methods of non-standard analysis.

On the other end of the spectrum, a proof which requires heavy mathematical machinery from multiple fields is typically referred to as a deep result, and would often be considered deep until an elementary proof is found.

Caution

The term “elementary” is sometimes reserved for a proof of a notable statement, so if a proof is elementary, it generally doesn’t mean that it’s either simple or trivial. An elementrary proof in number theory, for example, is simply one which does not resort to the methods of complex analysis (or other mathematical machinery).

Equivalent Claim

A statement which proves and can be proved from another statement (under a set of axioms and presuppositions). For example:

- An equivalent claim to the statement “n is divisible by 6” is the statement “n is divisible by both 2 and 3.”

- An equivalent claim to the completeness of real number is the least upper bound property, which states that every non-empty set of real numbers — if bound above — must have a least upper bound.

In general, if two statements $P$ and $Q$ are equivalent, then they are provable from each other with neither one of them being logically stronger or weaker than the other. In which case, one can also describe the situation by using statements such as “$P \iff Q$”, “$P$ iff $Q$” and “$P$ is necessary and sufficient for $Q$”.

Definition and Its Equivalent Conditions

When referring to an equivalent condition of a definition, the term “characterisation” is sometimes used, and when multiple characterisations are involved, a circle of equivalence can be also used (such as the case for the invertibility of a matrix).

Essentially Unique

A term used to describe a weaker form of uniqueness where all distinct objects satisfying a certain property are basically “equivalent” to each other. For example:

- The factorisation of an integer is essentially unique (i.e., up to the ordering of prime factors).

- There’s an essentially unique integer such that when divided by 10, has remainder 1 (i.e., up to the modulus).

- There’s an essentially unique set that is countably infinite (since all such sets are bijective to each other).

- There’s an essentially unique group with 3 elements (since all such groups are isomorphic to each other).

In general, an assertion of essential uniqueness presupposes some definition of “sameness”, which is often formalized using some equivalence relation. Because of that, the standard representative of an equivalence class is often used as a proxy of the said “unique” object — and to make clear of the fact that a quasi-uniqueness is at play.

Eventually

A term used to indicate that an object doesn’t have a certain property across all its ordered instances, but which will be after some instances (countably or uncountably many) have passed. For example:

- The sequence $n \mapsto \dfrac{3^n – 100}{4^n + 100}$ is eventually decreasing (e.g., when $n \ge 6$).

- The function $f(x)=2^x$ will eventually exceed the function $g(x)=x^{666}$.

- A sequence $a_n$ converges to $L$, if for all positive real numbers $\epsilon$, eventually $|a_n – L|< \epsilon$.

- A function $f(x)$ is said to be in the big-O of another function $g(x)$, if there exists a positive real number $M$ such that eventually, $|f(x)| \le Mg(x)$.

In general, the term “eventually” formalizes the long-term behavior of a mathematical object, and can be taken as a synonym of “when sufficiently large” or “after some point”. In fact, the point at which the property kicks in doesn’t even need to be known in advance — only that such a point does indeed exist.

Exceptional Object

A rare object (usually finite in number) with some desirable property that makes it different from most objects of the same class (e.g., regular polygons, platonic solids). It’s also different from both well-behaved and pathological objects in that it is an exception rather than the rule that’s not pathological.

Existence

A term used to assert the presence of an object satisfying a certain property, and is formalized using existential claims (i.e., claims of the form “there exists…”), and the logical quantifier $\exists$.

In general, to prove that an existential claim holds is to demonstrate, constructively or non-constructively, that object(s) with the property demanded in the claim exist — even though such objects might not be unique among those with the property.

Finite

That whose quantity pertains to a natural number or a real number — which might or might not include zero or the infinitesimals. Some example uses of “finite” in mathematics include:

- Finite area

- Finite variance

- Finite measure space

The opposite of finite is infinite, which — unlike the case with finite — is governed by a different set of arithmetical/operational rules (e.g., the first transfinite cardinal number $\aleph_0$ is such that $\aleph_0 + 1000 = 574 \cdot \aleph_0 = \aleph_0 + \aleph_0 = \aleph_0 \cdot \aleph_0 = \aleph_0$).

Folklore

A term used to refer to an unpublished mathematical result with no clear originator, which is well-circulated and well-understood to be true or useful among the specialists, but which is less so among those who are less entrenched in the field. For example:

- A theorem that is folklore is known as a folk theorem.

- A set of mathematical knowledge (e.g., definitions, propositions, proofs, techniques) that is folklore is known as folk mathematics (e.g.,. the folklore of ring theory).

In general, a folklore claim is most often obtained through conferences and word of mouth, though if one chooses to publish it with all the write-up, then it would lose its folklore status as a result.

Some Note on “Untrendy Folklore”

If a result is folklore, then it is understood to be currently in active circulation within the community. Were that to be not the case, then the result might be called wellknowable instead (a term coined by mathematician John Conway).

Frequently

An adverb used to describe a mathematical object which satisfies a certain property repeatedly (usually indefinitely) — for arbitrarily large arguments or instances. For example, one could say that:

“The sequence $a_n = (-\frac{1}{2})^n$ is frequently in the interval $(0, \frac{1}{1000000})$.”

If, on the other hand, the property is satisfied for all arguments after a certain point, then the term “eventually” is usually preferred instead.

Generalization

A form of abstraction where one goes from a set of simpler cases to higher-order instances, and can manifest in mathematical thinking in different ways (e.g., broadening the scope of a claim, solving a slightly more complex problem set). Some examples of generalization in mathematics include:

- Expanding the MacLaurin series into Taylor series

- Expanding the formula of $(1+x)^n$ into the binomial formula of $(x + y)^n$

In general, generalization is both advantageous and disadvantageous, in that while it can make a claim less concrete and less visualizable, it can also make it more powerful and more applicable as a result.

Global

A term used to indicate that a mathematical object satisfies a property across its entire object (e.g., global extremum, (global) uniform continuity, global topology, global cover). It is similar to the term “absolute”, and is to be contrasted with the term “local” — which is used to indicate that the property is only satisfied at some portions of the object.

Hand-waving

The act of demonstrating the validity of a claim without providing an entirely rigorous argument for its validity, and which typically involves the use of unrepresentative examples, unjustified assumptions, key omissions and faulty logic.

(For “proof methods” related to hand-waving, see proof by intimidation and proof by example.)

Expectedly, hand-waving is generally regarded as a bad mathematical practice, since it tends to distract one from the legitimate flaws one is making, and can be especially devastating when the unjustified assumptions are false. However, that’s not to say that it can’t be useful at times in expository work and seminars, as Wikipedia puts:

“[C]ompetent, well-intentioned researchers and professors also rely on explicitly declared hand-waving when, given a limited time, a large result must be shown and minor technical details cannot be given much attention—e.g., “it can be shown that z is an even number”, as an intermediary step in reaching a conclusion.”

The Opposite of “Hand-waving”

As much as hand-waving can be problematic, so can its opposite. In fact, in mathematical publishing and pedagogy, the act of pursuing a solution through a dry, mechanical and unimaginative line of reasoning is known as nose-following, and can be the antithesis of interesting mathematics.

Heuristics

A series of general, trial-and-error-based strategies for solving mathematical problems which — while not necessarily optimal — can be cost-effective in yielding a satisfactory solution given the amount of invested time and effort. Some of most used heuristics in mathematics include:

- Giving a visual representation to a problem

- Making an assumption or a conjecture

- Reasoning forward and backward

- Making an educated guess (before refining the result)

- Solving a simplified, more concrete version of a problem

In general, heuristics and algorithms are similar in that both constitute some form of mathematical procedures, but are different in that the former prioritizes higher-order thinking over the actual steps — and as such might require a bit more mental flexibility and creativity.

On the other hand, a heuristic argument is generally one which — while pedagogically useful and seemingly convincing — makes a few key oversimplifications which disqualify it from a rigorous proof (e.g., establishing the derivative of $f^{-1}(x)$ by differentiating both sides of the equation $f^{-1}(f(x))=x$).

Identity

A mathematical claim in the form of an equation — usually with some variables — which has been shown to be true for all values of the variables within a certain range of validity. Some examples of identities in mathematics include:

- Algebraic identities

- $(x+y)^4=x^4 + 4x^3y + 6x^2y^2 + 4xy^3 + y^4$, for all $x,y\in\mathbb{C}$

- Trigonometric identities

- $\displaystyle \tan(x+y)=\frac{\tan x+\tan y}{1-\tan x \tan y}$, for all $x, y \in \mathbb{R}$ with $x, y, x+y \ne \dfrac{\pi}{2}$ (in mod $\pi$)

- Logarithmic identities

- $\displaystyle \ln \sqrt[p]{x} = \frac{\ln x}{p}$, for all $x, p \in \mathbb{R}_+$

- Combinatorial identities

- Vector identities

In abstract algebra, the term “identity” can be also used to denote an element which leaves all elements of a set invariant under some operation (e.g., additive identity, multiplicative identity).

Identity vs. Inequality

If an ordering relation (i.e., $<, >, \le, \ge$) is found at the place of the $=$ symbol, then an inequality — instead of an identity — is involved. Similar to other results in mathematics, both identities and inequalities can be often used to greatly simplify a derivation or a proof.

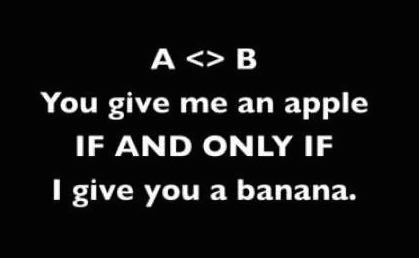

If and Only If

A phrase associated with the logical connective $\leftrightarrow$ (i.e., the biconditional), and is used to conjoin two statements which are logically equivalent. Since it is composed of both the “if” portion (i.e., sufficiency) and the “only if” portion (i.e., necessity), a statement of the form “X if and only if Y” can be also rephrased as “X is necessary and sufficient for Y”, or “X is equivalent to Y”.

In general, a biconditional of the form $X \leftrightarrow Y$ can be proved in two ways:

- By proving the implication and its converse (e.g., $X \rightarrow Y$ and $Y \rightarrow X$)

- By proving the implication and its inverse (e.g., $X \rightarrow Y$ and $\neg X \rightarrow \neg Y$)

Whichever the case, once the biconditional is established, $X$ and $Y$ would be deductively interchangeable — even if they might have very different meaning.

Iff and Its Origin

In some occasions, the term “iff” can be also used as a shorthand for “if and only if”. Allegedly invented by Paul Halmos around the mid-20th century, the term “iff” has now achieved a wider adoption and can be pronounced as either “if and only if” — or as “if” with a prolonged “f”.

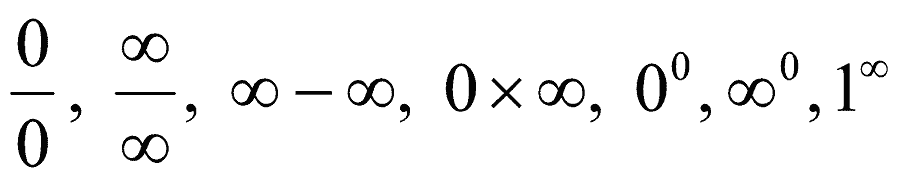

Indeterminate

A term typically used to refer to a mathematical expression capable of assuming multiple values, though its actual meaning is generally quite precise and dependent upon context. For example:

- In abstract algebra, an indeterminate is a variable used to generate mathematical elements and structures (e.g., polynomial ring $\mathbb{R}[x, y]$, formal power series).

- In algebra, an equation or a system of equations is called indeterminate — or underspecified — if it has multiple solutions.

- In analysis, the indeterminate forms are a series of mathematical expressions involving $\infty$, $1$ and $0$ which are usually left undefined — because of their propensity to assume different limits (whenever they exist).

Note on Indeterminate Form and the Actual Limit

In general, just because the limit of a mathematical expression corresponds to an indeterminate form doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. In fact, such limits can often be determined indirectly through a combination of algebraic manipulation and L’Hôpital’s rule.

Inequality

A mathematical statement which makes a non-equal comparison between two mathematical expressions, and which can be further categorized into the following three types:

- Loose inequality: when the comparison symbol is $\le$ or $\ge$.

- Strict inequality: when the comparison symbol is $<$ or $>$.

- Inequation: when the comparison symbol is $\ne$.

In general, inequalities tend to be in place when an equality cannot be readily established (or is otherwise inapplicable), and are quite often used to provide a sharp bound for some mathematical expression of interest. Some prominent inequalities in mathematics include:

Similar to equations, inequalities can be put into chain notation (e.g., $\big| |x|-5 \big| \le |x-5| \le |x| + 5\,$) and manipulated through elementary operations, even though their rules of operations might be slightly different — due to the fact that they’re more approximative in nature.

Infinite

An adjective used to refer to the general quality of being boundless (e.g., infinitely small, infinitely close), and is mostly used to describe an object whose quantity or limit is larger than any natural number or real number (e.g., infinite series, infinite length, infinite variance, infinitely-dimensional space).

In many scenarios, infinity is used solely as a concept (e.g., potential infinity as in infinite limits) rather than as an actual number (e.g., actual infinity), though it can also be formalized as actual numbers in the following two ways:

- Infinities as extended real numbers: $+\infty$ and $-\infty$

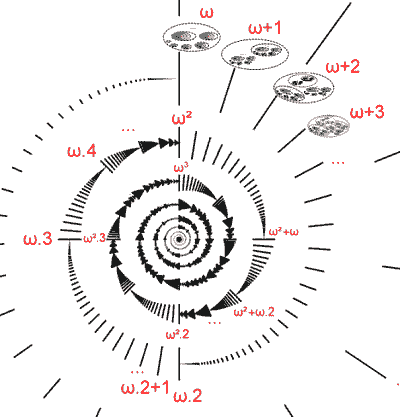

- Infinities as sets and transfinite numbers:

- Countable infinity

- Uncountable infinities

- Transfinite cardinals (e.g., $\aleph_0$, $\aleph_1$)

- Transfinite ordinals (e.g., $\omega$, $\omega^{\omega}$)

Historically, the concept of infinity has fascinated many and led to many “paradoxes” (e.g., Zeno’s paradoxes, Galileo’s paradox, Hilbert’s paradox, Cantor’s paradox), thereby illustrating that common notions about finite objects are often misleading when it comes to the infinite (for whom the results are often intuition-defying).

Infinitely vs. Arbitrarily

While the terms “infinitely” and “arbitrarily” are both used to refer to some form of boundlessness, they are different in that the former often describes a state of actual infinity (e.g., infinitely large numbers), while the latter a state of potential infinity (e.g., arbitrarily large numbers).

In General

A term used to indicate that a generalization is under way. When used informally, it can be taken to mean “most” (e.g., “in general, integers are composite”), though in many scenarios, it is to be interpreted as “apply to all instances of a broader class” or “apply to all subcases in question”, as in:

“Therefore, $2n^3+3n^2+n$ is divisible by 6 in general.”

In some occasions, the phrase “in general” can also be found at the end of a proof (e.g., proof by induction, proof by cases) as a standard concluding remark.

Intuition

A series of mathematical foresight, know-how and savviness that — while very difficult to pinpoint — allow one to “connect the dots” and tackle mathematical challenges more fruitfully with less wasted effort.

Despite its instinctive nature, mathematical intuition is often a product of accumulated knowledge and experience, and can be indicative of historical patterns and connections, as an anonymous mathematician puts on Quora:

You are often confident that something is true long before you have an airtight proof for it (this happens especially often in geometry). The main reason is that you have a large catalogue of connections between concepts, and you can quickly intuit that if X were to be false, that would create tensions with other things you know to be true, so you are inclined to believe X is probably true to maintain the harmony of the conceptual space. It’s not so much that you can imagine the situation perfectly, but you can quickly imagine many other things that are logically connected to it.

Like rigor, intuition is often considered to be an integral part of mathematics, as it allows one to find the answer to a problem before solving it (a recurring theme in the history of mathematics), and helps imbue mathematics with a series of qualities that set it apart from some meaningless manipulations of symbols.

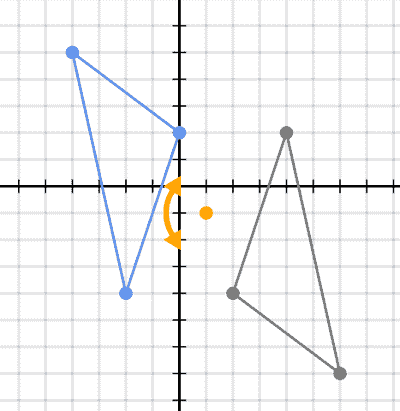

Invariance

The property of a mathematical object to remain unchanged after an operation or a transformation. For example:

- A triangle is invariant under 3 rotations (as in the “swapping” of edges).

- An even function is invariant under reflection about y-axis.

- An angle is invariant under scaling.

- A symmetric matrix is invariant under matrix transposition.

- A determinant is invariant under “absorption” (i.e., the addition of a multiple of a row to another).

- The real part of a complex number is invariant under complex conjugation.

- A variance is invariant to linear changes in the random variable.

In geometry and other visually-based topics, invariance is often known under the name of symmetry (e.g., invariance under translation, scaling, reflection and rotation), though it can also occur in other topics such as algebra, topology, statistics, and discrete mathematics, and might even be regarded as a fundamental pattern of the mathematical universe.

Lemma

A minor, relatively-easy-to-prove claim which is often used as a stepping stone for proving major results (e.g., the use of Euclid’s lemma in the proof of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic). For that reason, a lemma is also known as an “auxiliary theorem” or a “helping theorem” — even though it can also occasionally turn into a major result and take on a life of its own (e.g., Zorn’s lemma).

Local

A term used to indicate that a mathematical object satisfies a property at some limited portions of the object — or from the point of view of some narrow, immediate surrounding. Some examples of local in mathematics include:

- Local extremum

- (Local) continuity

- Local view of surface

- Local flow

- Local topology

- Local solution

- Local optimum

- Local field

In general, the term “local” is similar in usage to the term “relative“, and is to be contrasted with the term “global” — which is used to indicate that the property is satisfied across the entire domain of interest.

The Duality Between Local and Global

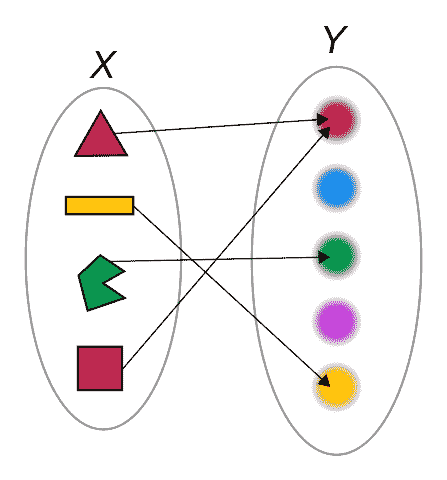

Mapping

A mapping, also known as a map, is simply a general function from a source to a target. The term originates from the idea of “mapping” each element of the source to a unique element in the target — such as the case of the function from $\{1, 2\}$ to $\{2, 3, 4\}$ with $1 \mapsto 2$ and $2 \mapsto 3$.

Unlike a function — which can be interpreted as a term from analysis — the source and the target of a mapping doesn’t need to be related to numbers. As a result, a mapping might be known under different names depending on the context where it’s found (e.g., linear transformation, continuous map, Laplace transform, morphism).

Mathematical Fallacy

A mathematical inference or derivation which violates the condition of its applicability. It’s similar to a logical fallacy in logic, though its context is more math-specific and can even go beyond simple mistakes to include some with elements of concealment and deception (as in the case of pseudomathematics). Some examples of common mathematical fallacies include:

- Division by zero (e.g., dividing by $(x-y)$ when $x=y$)

- Anomalous cancelling (e.g., $\frac{1\cancel{6}}{\!\!\cancel{6}4} = \frac{1}{4}$)

- Misapplication of properties (e.g., $\sqrt{-1 \cdot -1} = \sqrt{-1} \cdot \sqrt{-1}$)

- Misuse of induction (e.g., the horse paradox)

While mathematical fallacies can compromise the validity of an argument, they alone generally do not provide sufficient ground for accepting or rejecting a statement. In fact, it’s often possible for an argument to reach the correct conclusion while committing some mathematical fallacy, in which case the argument is known as a howler (and is often used with a sense of humor).

Mathematical Machinery

A colloquial term for the advanced theorems, methods and techniques developed over the years — which can be used to tackle future problems in the same field or a different field with relative ease.

While heavy mathematical machinery can be immensely useful in application, they can also contribute to the degradation of elegance in a proof. As a result, elementary proofs are almost always sought after — even after a claim is proved.

Mathematical Maturity

The quality of having a general understanding and mastery of the way mathematicians operate — and the language they use to communicate ideas. These include, among others:

- The ability to identify and state mathematical patterns

- The ability to raise interesting mathematical questions

- The ability to carry out generalizations

- The ability to understand and make use of higher mathematical jargon

- The ability to make sound judgments on the quality and the validity of a proof

- The ability to think through the implications of a definition or a proposition

- The ability to fill in the preliminaries on one’s own

- The ability to construct and present a proof or a disproof of a typical claim

In general, mathematical maturity allows one to operate intellectually in an independent, standalone manner, and like mathematical intuition, can be a product of both knowledge and experience.

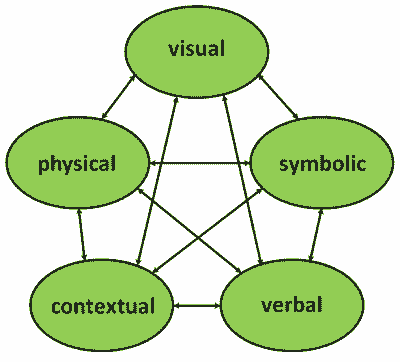

Mathematical Representation

In mathematical education, a representation is one which encodes a mathematical idea or a relationship. It can occur as both internal (e.g., mental/cognitive construct) and external forms, and can be used to facilitate thinking, problem solving and communication in general. Some prominent examples of representation in mathematics include:

- Diagram

- Table

- Number line

- Arrangement

- Cartesian graph

- Physical model

- Spatial visualization

- Algebraic expression

- Verbal mnemonic

While representations can come in all shapes and forms, having multiple representations of the same mathematical idea (e.g., definitional vs. computational formula of variance, algebraic vs. combinatorial proof of Pascal’s rule) can still be very useful — as it allows one to tap into new insights and perspectives that might be hard to obtain otherwise.

Formal Representation

In some abstract branches of mathematics, the term “representation” has a similar but more technical underpinning, and is generally used to assert the similarity or the equivalence between two structures using concepts such as homomorphism and isomorphism. For example:

- A representation theorem is a theorem which states that every algebraic structure — with a certain property — is isomorphic to another structure.

- In abstract algebra, representation theory is a field which studies abstract algebraic structures by representing their elements as linear transformations.

- In graph theory, the behaviors and properties of a graph can be often studied by representing it as its isomorphic algebraic counterparts (e.g., adjacency matrix, Laplacian matrix)

Mathematical Structure

A mathematical object consisting of a set along with some additional features on the set (e.g., operation, relation, metric, topology). Some eminent mathematical structures include, among others:

- The group of integer under addition (i.e., $(\mathbb{Z}, +)$)

- The partition of integers, as induced by the congruence relation with modulus $11$

- The ordered field of real numbers (i.e., $(\mathbb{R},+, \times, <)$)

- The 3-dimensional Euclidean vector spaces with the taxicab metric

Across structures, certain mappings such as homomorphism and isomorphism allow one to categorize different structures as “similar” or “identical”, and since structures often lie at the root of mathematics, the study of structures can also reveal fundamental patterns that are transferable or generalizable to other fields.

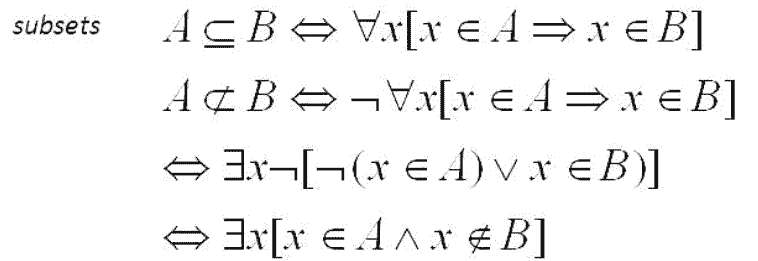

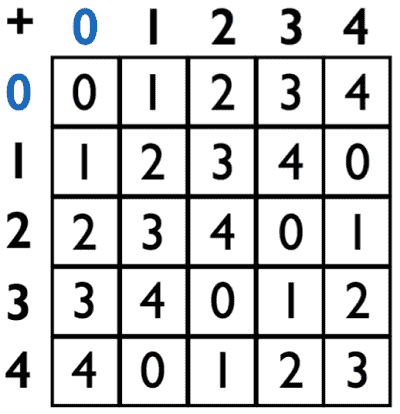

Modulo

A term derived from the Latin word modulus (i.e., a small measure), and is used to mean that two mathematical objects — though distinct — could be made to be equivalent if their differences were accounted for by an additional factor.

For example, one could say that “1 and 3 are congruent modulo 2”, or more generally:

$A$ and $B$ are equivalent — modulo an equivalence relation $R$.

In terms of usage, the term “modulo” is similar to the term “up to” — though the latter tends to be more formal in nature and sometimes even wider in scope.

In computing, the term “modulo” can also refer to the modulo operation — a binary operation denoted by $\mathrm{mod}$ which returns the remainder of a Euclidean division. More specifically, given a dividend $n$ and a non-zero divisor $d$, the expression $n \mathrm{\ mod \ }d$ refers to the remainder of the division $n \div d\,$ (e.g., $101 \mathrm{\ mod \ }9 = 2$).

Natural

An occasionally-informal substitute for the term “canonical“, that generally has very little to do with nature. Aside from its occurrences in the common mathematical parlance (e.g., natural number, natural logarithm), it’s generally used to describe a transformation whose description holds independently of choices (e.g., natural transformation).

Unlike canonical, what’s designated as natural is often not unique — if not loosely defined. Though in some occasions, both terms could indeed be used interchangeably (e.g., canonical vs. natural map).

Necessity

“Logical inevitability”, or the quality of being a logical consequence. For example:

- The claim “P is necessary for Q” can be taken to mean “the truth of P is guaranteed by the truth of Q”, and can be also rephrased as “P is implied by Q”.

- The necessity part of the biconditional $A \leftrightarrow B$ usually refers to the claim $A \leftarrow B$ (which can be read as “$A$ is a necessary condition for $B$”, or “$A$, if $B$”).

In general, logical necessity corresponds to the “if” part of an “if and only if” statement, and is by no means a guarantee that logical sufficiency will take place. Were the sufficiency part to also follow through, then one would remark by saying that an equivalent claim is at play.

Null

An adjective frequently associated with the concept of “nothing“, though it’s usually attached to a noun to mean something more specific. For example:

- A null element is an element that generalizes the concept of zero (e.g., null matrix).

- A null vector is the vector of length 0 (among other meanings).

- A null set is the set with no element (among other meanings).

- A null space of a linear mapping — also known as a kernel — is the set of vectors which map to the null vector under that mapping.

- A null hypothesis is the status quo hypothesis that there’s nothing significantly different happening, and is one which is presumed to be true until proven otherwise.

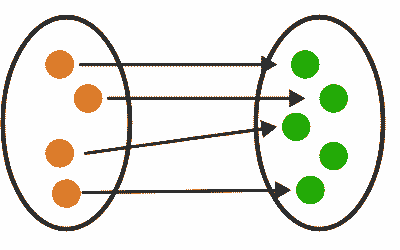

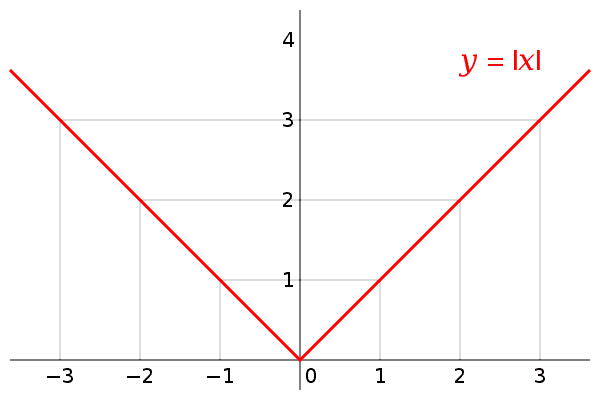

One-to-One

The quality of a function to map distinct elements in the domain to distinct elements in the codomain (e.g., the real-valued function defined by the assignment $x \mapsto 2x+1$). In which case, the mapping is also known as an injective function — or an injection for short.

From a set theory standpoint, if a mapping from $A$ to $B$ is one-to-one, then the “size” of $B$ is at least as large as that of $A$. By removing the unmapped elements in the codomain, one can also transform a one-to-one function into a one-to-one correspondence as well.

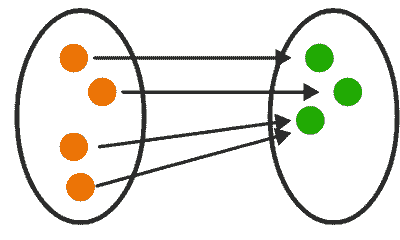

One-to-One Correspondence

A function that is both one-to-one and onto (i.e., one which pairs up the members of the domain perfectly with the members of the codomain), and is also known as a bijective function or a bijection for short. Some examples of one-to-one correspondences in mathematics include:

- The identity function (on any set)

- The linear functions on $\mathbb{R}$ described by the assignment $x \mapsto ax+b$ (where $a \ne 0$)

- The arctan function from $\mathbb{R}$ to $\displaystyle \left(-\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}\right)$

- The exponential functions from $\mathbb{R}$ to $\mathbb{R}_+$

In general, a one-to-one correspondence indicates that the underlying function is invertible, and is often used to show that the domain and the codomain are of the same “size”.

Onto

A term originated from the projection of images in optics, and is used to indicate that a function leaves no element unmapped in the target/codomain (e.g., the identity function maps a set onto itself). In which case, the mapping is also known as a surjective function — or a surjection for short.

From a set theory standpoint, if a set $A$ maps onto a set $B$, then the “size” of $A$ is at least as large as that of $B$. In the case where $A$ doesn’t map onto $B$, surjectivity can still be induced by removing the unmapped elements in $B$.

Operation

A function which takes one or more inputs (usually from the same set) to a well-defined output, with the most common ones being the unary operations (i.e., operations with 1 input) and the binary operations (i.e., operations with 2 inputs). Some prominent operations in mathematics include, among others:

- Arithmetic operations

- Reciprocal function

- Factorial function

- Root functions

In general, the study of operations are dominated by the study of unary and binary operations, as they often possess properties which make them relatively easier to handle (e.g., associativity, commutativity, idempotence). By combining different operations together, more sophisticated operations can be also formed — which might lend themselves further study and analysis as well.

Paradox

A self-contradicting statement — in the sense that it would be true if false and false if true. Some examples of (true) paradoxes in mathematics include:

- The liar’s paradox: the statement “this statement is false” cannot be assigned a truth value — since it’s true precisely when it’s false.

- Russell’s paradox: the set of all sets that are not element of themselves cannot exist — since it would be an element of itself precisely when it is not.

Historically, the discovery of a paradox often leads to a crisis of foundation in mathematics, and often calls for a resolution to the paradox by reworking the underlying axioms and definitions of the field (e.g., axiomatization of set theory, formalization of real analysis).

Pathological

The quality of a mathematical object to possess deviant, irregular properties — that make it different from a typical object (or what’s considered as a typical object) in the same category. Some examples of pathological object in mathematics include:

- The irrational number $\sqrt{2}$

- The Dirichlet’s function (a function that is continuous nowhere)

- The Weierstrass’s function (a function that is continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere)

- The Cantor set (a subset of $[0,1]$ with measure zero that is uncountable)

In general, pathological objects tend to appear like the exception rather than the rule, though they could often be shown to be more prevalent than originally thought, and might even lead to a new paradigm shift and development within the field.

The opposite of pathological is well-behaved, which — like pathological — is also subject to personal interpretation, surrounding context and cultural influence.

Proof by Brute Force

An extreme form of proof by cases — where a claim is proved by breaking it down into all the possible cases in great detail (e.g., the first computer-assisted proof of the four color theorem in 1976).

While such an approach constitutes a perfectly legitimate method for proving a claim, it can also sometimes be considered as the antithesis of elegance — and might even reflect a lack of personal and collective understanding on the subject matter.

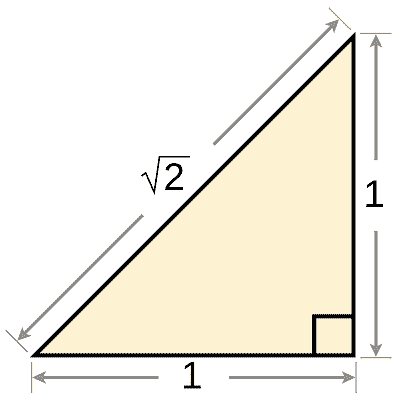

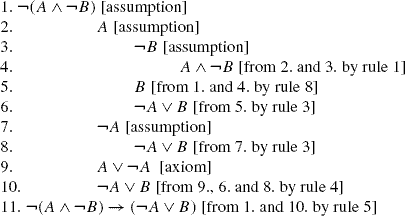

Proof by Contradiction

An indirect method of proof that attempts to prove a claim by proving that the opposite will lead to a contradiction. For that reason, the method is also known as “reductio ad absurdum” — or “reduction to absurdity” in Latin.

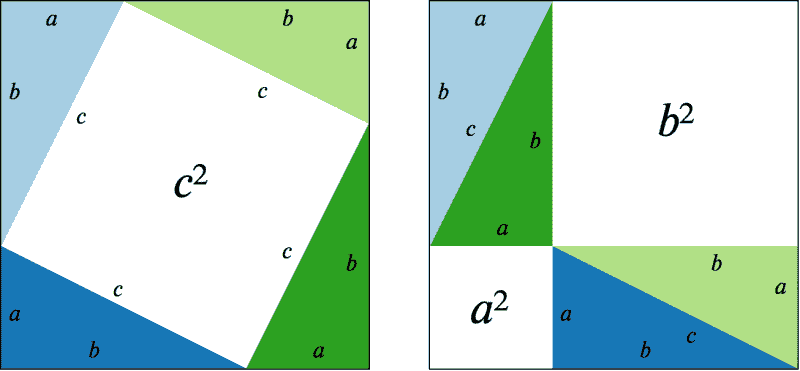

A celebrated example used to illustrate the inner working of proof by contradiction involves the proof of the irrationality of $\sqrt{\mathbf{2}}$, where one is taken from the initial assumption that $\sqrt{2}$ can be expressed as a ratio of two co-prime integers — to the ultimate conclusion that the said integers are actually not coprime after all.

When occurred in texts, a proof by contradiction is usually prefaced by clauses such as “by way of contradiction” (BWOC), “suppose not” and its variants. It is not to be confused with proof by contraposition, which is similarly indirect but involves no contradiction at all.

Note on the Validity of Proof by Contradiction

The underlying argument behind a proof by contradiction presupposes that every claim is either true or false (i.e., law of excluded middle). As a result, a small minority of people who do not ascribe to this presupposition (e.g., intuitionists) are forced to reject the validity of a proof by contradiction as well.

Proof by Example

A humorous term used to refer to an argument which attempts to illustrate the validity of a claim through cases and examples — rather than a full-fledged proof. For example, one might say that:

“Since 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17… are all odd, all prime numbers must be odd.”

In many cases, a “proof by example” is itself an example of a logical fallacy, though there are at least 2 cases where that might not apply:

- The claim is such that it only requires a small amount of examples to be proved (e.g., existential claim).

- The “proof” actually does contain the key ideas needed to generalize it into a full-fledged proof.

For other similar “proof techniques” that could be potentially fallacious, see hand-waving and proof by intimidation.

Proof by Induction

A proof technique employed to show that a claim holds for all natural numbers (or any other set that is inductively defined), and which typically involves the following two steps:

- Base case: Showing that the claim holds for a minimal instance (e.g., proposition $P(n)$ holds when $n=1$).

- Inductive case: Showing that by assuming that the claim holds for an arbitrary instance (i.e., inductive hypothesis), one can deduce that the claim will also hold for the next instance (e.g., $P(n) \implies P(n+1)$ for all $n \in \mathbb{N}$).

In general, a standard inductive proof (i.e., weak induction) is useful in that it reduces the proof of infinitely many instances into two steps. By modifying the standard induction slightly, it is also possible to use induction to prove claims of a different form as well (e.g., strong induction, reverse induction, prefix induction, multi-variate induction, structural induction, transfinite induction).

Caution

As misleading as it sounds, the reasoning behind a proof by induction is actually deductive, since it involves a method of inference which takes one from a true statement to another, and hence the saying “mathematical induction is not inductive.”

Proof by Infinite Descent

A proof method typically used to show that a claim cannot possibly hold for any number, by showing that if it were to hold for some number, then the same must be true for some smaller number, leading to an infinite descent and ultimately a contradiction.

A quintessential example of proof by infinite descent involves the celebrated proof of the irrationality of $\sqrt{\mathbf{2}}$, where by assuming that $\sqrt{2}$ is expressible as a ratio of two integers $p$ and $q$, one is led to the conclusion that $\sqrt{2}$ is also expressible as a ratio of another pair of integers $\frac{p}{2}$ and $\frac{q}{2}$ (which, as we know, cannot continue indefinitely, since the set of even natural numbers has a least element).

Structurally, proof by infinite descent is a hybrid method combining both proof by contradiction and proof by induction, and is often found in the form of proof by minimal counterexample to make the presentation easier and more intuitive.

Note on the Applicability of Infinite Descent

The method of infinite descent is only applicable if the set in question is well-ordered. As such, it’s often used in claims where natural numbers are involved (even though it could also be adapted to claims where no number is actually involved as well).

Proof by Intimidation

A humorous term used to refer to a specific form of hand-waving, where one attempts to establish the validity of a claim by marking it as obvious or trivial, Some common phrases used to initiate or finalize a proof by intimidation include:

- “Clearly…”

- “It is self-evident that…”

- “It can be easily shown that…”

- “… doesn’t warrant a proof.”

- “The proof is left as an exercise.”

While a proof by intimidation often sounds patronizing at first, it can also be regarded as a key hint indicating that a proof can be obtained fairly quickly and routinely — by applying the standard methods in the context where it’s given.

Origin of Proof by Intimidation

According to Gian-Carlo Rota, the term “proof by intimidation” was first coined by Marc Kac to describe some lectures of William Feller, who occasionally asked the objectors to leave the classroom for pointing out some “glaring mistakes”.

Proof from First Principles

A proof of a claim (usually a fairly common one) which only relies on the basic definitions, properties and axioms of the field, and which does not appeal to higher-order theorems or methods that can make the proof almost trivial. Some examples of proof from first principles in mathematics include:

- The proof of the commutativity of addition from Peano’s axioms

- The proof of the product rule (for derivative) using limits

- The proof of the value of a definite integral using Riemann sums

In general, a proof from first principles is beneficial in that it allows one to present the result in a logically straight-forward manner, though it can also end up making the proof harder and less manageable — than relying on well-established theorems that are higher up in the logical hierarchy.

Proof from Axioms vs. Proof from First Principles vs. Elementary Proof

In general, a proof comes with varying degrees of “elementariness“, with a proof from axioms being the strictest, and a proof from first principles being the second — as it might allow the use of certain properties that are considered part of the “basic repertoire”.

On the other hand, an elementary proof is simply a proof whose approach does not require a significant detour outside the field (or a significant development within the field). As such, it is actually the least strict one among the three types of proof.

Proper

The property of being a non-trivial, common instance of a mathematical object (e.g., proper fraction, proper subset, proper divisor, proper class). In some occasions, the term “strict” can be also used to the same effect.

Proposition

A mathematical statement whose truth value is well-defined, and whose perceived importance is generally neutral. For example, one proposition in real analysis states that:

“There is an irrational number between every pair of distinct real numbers.”

Structurally, propositions can be regarded as the building blocks of both propositional logic and mathematics, and might be known under different names depending on their functions and purposes (e.g., axiom, lemma, theorem, corollary, conjecture).

Pseudomathematics

The mathematical version of pseudo-science, where one attempts to advance a set of questionable mathematical beliefs by using seemingly-mathematical methods that do not adhere to the standard of rigor abided by the mathematical community. These include, among others:

- Disproving commonly accepted claims

- Changing the value of $\pi$ or other mathematical constants

- Claiming that $0.999\ldots \ne 1$

- Proving what has been previously proved to be impossible (e.g., squaring a circle)

- Denying commonly accepted mathematical terms and methods

- Rejecting a proof by contradiction as unmathematical

- Refusing the validity of Cantor’s diagonal argument or Gödel’s incompleteness theorems

- Rejecting irrational/transcendental/complex numbers on the basis of one’s belief

In general, pseudomathematics often involves a great deal of mathematical fallacies, that are executed in a way that’s more organised and misleading than some genuine attempts with unintended mistakes. For that reason, it is also colloquially known as mathematical crankery — a topic studied extensively by mathematician Underwood Dudley.

Q.E.A.

The acronym for quod est absurdum (“which is absurd“) — a Latin phrase used in the old days to conclude a proof by contradiction. In the modern days, its usage is increasingly being replaced by the symbol ⨳, though other symbols, such as ※ or $\Rightarrow \Leftarrow$, are equally well-adopted as well.

Q.E.D.

The acronym for quod erat demonstrandum (“which was to be demonstrated“) — a Latin phrase frequently used to conclude a mathematical proof in print publications. In the modern days, its usage is increasingly being replaced by phrases such as “as desired” and “as expected”, and symbols such as □ and ■ (Halmos’ tombstone).

Q.E.D. vs. Q.E.F.

Another variant of Q.E.D. is the acronym Q.E.F., which stands for quot erat faciendum (“which was to be done”) in Latin. Unlike Q.E.D. (which is used to indicate the end of a proof), Q.E.F. corresponds to the phrase used by Euclid to indicate that a geometrical construction is complete.

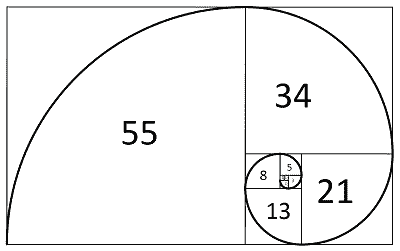

Recursion

The phenomenon whereby a mathematical expression or a procedure is expressed as some instances of itself — in a way that does not involve any circularity or infinite loop. Because of that, a recursion is often framed using the following two clauses:

- Recursive clause: the central clause determining how most of the instances are to be generated.

- Base clause(s): the auxiliary clause(s) determining the initial conditions of the expression — so as to prevent an infinite regress.

In general, recursion is a recurring concept in fields such as number theory, mathematical logic, discrete mathematics and fractal geometry, where some of the examples might include, among others:

- The recursive definition of factorial

- $0! \stackrel{df}{=} 1$

- $n! \stackrel{df}{=} n (n-1)!$ for $n\ge 1$.

- The recursive definition of natural number

- $1 \in \mathbb{N}$

- $n \in \mathbb{N} \implies n+1 \in \mathbb{N}$

- The recurrence relation for Fibonacci numbers

- $F(1)=1$, $F(2) = 1$

- $F(n)=F(n-1)+F(n-2)$ for $n\ge3$.

- The definition of Cantor ternary set

- The Euclidean algorithm for the greatest common factor

In some occasions, it might be possible to convert a recursive expression into a non-recursive one that does not include any instance of itself. In which case, one would describe this by saying that a closed-form expression is involved — which in many cases is advantageous due to the simplicity in evaluating each of its instances.

When an object is defined recursively (e.g., functions, sets, fractals), it is also said to be inductively defined. An inductive definition allows one to spell out an object elegantly by emphasizing its underlying pattern, while an inductively-defined structure allows a claim based it to be proved using structural induction.

Regular

An adjective similar to “nice” and “well-behaved” that is used to describe an object satisfying a list of prevailing conditions, though the actual conditions are generally quite precise and dependent upon the context where it’s given (e.g., regular polygon, regular functions, regular numbers, regular elements, regular graphs, regular space).

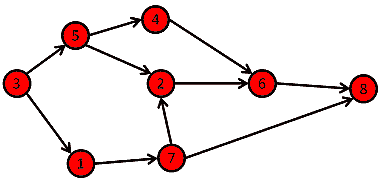

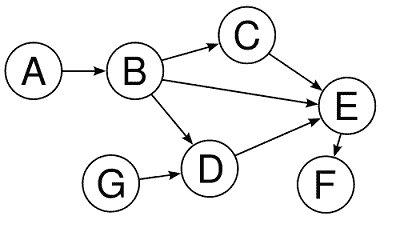

Relation

A collection of n-tuples (i.e., an ordered list of n objects), with the most studied special case being the binary relation — a set of ordered pairs used to indicate which exact object is related to which.

For example, the divisibility relation $R \subseteq \mathbb{Z} \times \mathbb{Z}$ is the relation such that:

For all $x, y \in \mathbb{Z}$, $(x,y)$ is in the relation $R$ precisely when $x$ is a divisor of $y$.

In general, the study of relations is dominated by the study of binary relations, as the latter can often be visualized through mathematical graphs and tend to possess properties which make them deductively handy (e.g., reflexive, anti-symmetric, transitive, left-total).

In fact, by packaging some of these properties together, more sophisticated relations — such as functions, equivalent relations and order relations — can also be formed, which might lend itself to further study.

Rigor

The quality of employing a series of deductive inferences in a way that is precise, unambiguous and valid at each step. To be rigorous is to uphold the standard of deductive validity, and to carry out the whole reasoning in a way that is verifiably truth-preserving (e.g., through algorithmic proof-checking).

A framework for understanding rigor in mathematics is to see it through the lens of a formal proof — which is a finite sequence of mathematical sentences with the last one being the claim to be proved. In this context, every sentence in the sequence must fall into one of the following categories:

- Premises/Assumptions

- Axioms

- Results derived from the application of a valid inference rule

While rigor in this strict format is relatively rare in the standard mathematical discourse (and might even be off-putting in some scenarios), laying out the details of a proof in an explicit and systematic way is still considered a good practice — as it can help one identify and mitigate any fallacy that might come along the way (e.g., hand-waving, misuse of notation, proof by example, proof by intimidation).

Rigor in the History of Mathematics

Historically, the standard of rigor tends to increase over time as one discovers new unarticulated assumptions, paradoxes and dubious ambiguities. This would lead to a series of interesting developments related to the foundation of mathematics, which include, among others:

- The development of mathematical analysis from calculus in the early 19th century

- The arithmetization of analysis in the mid 19th century

- The reduction of arithmetic to set theory in the late 19th century

- A general trend towards rigorization and axiomatization in the 20th century

Sharp

An adjective indicating that a constraint is optimal or extremal — in the sense that it cannot be further reduced without losing its status (e.g. sharp upper bound, sharp inequality). In some occasions, the term “tight” could also be used to the same effect.

Singularity

A point at which a mathematical object — such as an equation or a surface — ceases to be well-behaved and deviates from its usual behaviors. For example:

- The real-valued reciprocal function $f(x)=\frac{1}{x}$ has a singularity at $x=0$, where it “blows up” to $\pm\infty$ and is hence undefined.