In the world of complex numbers, as we integrate trigonometric expressions, we will likely encounter the so-called Euler’s formula.

Named after the legendary mathematician Leonhard Euler, this powerful equation deserves a closer examination — in order for us to use it to its full potential.

We will take a look at how Euler’s formula allows us to express complex numbers as exponentials, and explore the different ways it can be established with relative ease.

In addition, we will also consider its several applications such as the particular case of Euler’s identity, the exponential form of complex numbers, alternate definitions of key functions, and alternate proofs of de Moivre’s theorem and trigonometric additive identities.

Note

This Euler’s formula is to be distinguished from other Euler’s formulas, such as the one for convex polyhedra.

Prefer the PDF version instead?

Get our complete, 22-page guide on Euler’s formula—in offline, printable PDF format.

Table of Contents

Euler’s Formula Explained: Introduction, Interpretation and Examples

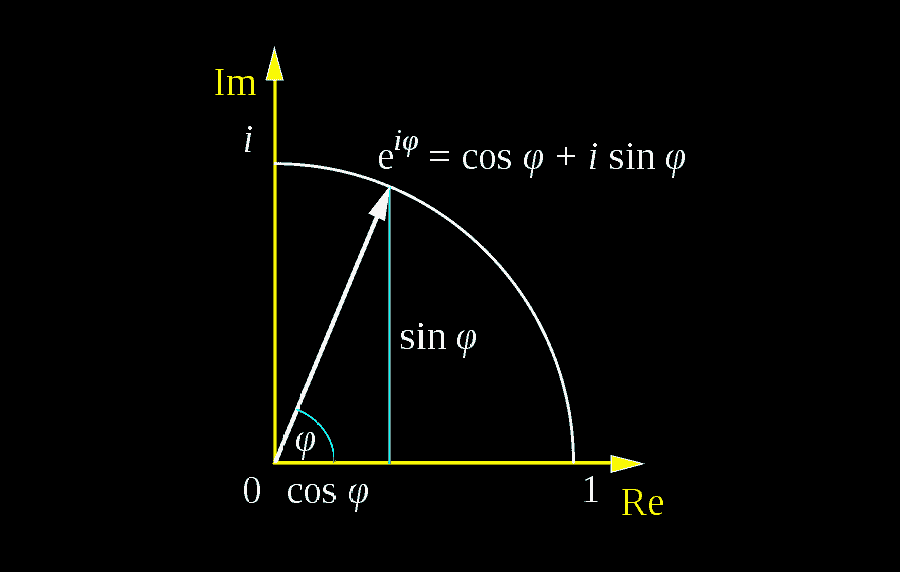

So what exactly is Euler’s formula? In a nutshell, it is the theorem that states that

$e^{ix} = \cos x + i \sin x$

where:

- $x$ is a real number.

- $e$ is the base of the natural logarithm.

- $i$ is the imaginary unit (i.e., square root of $-1$).

Note

In this formula, the right-hand side is sometimes abbreviated as $\operatorname{cis}{x}$, though the left-hand expression $e^{ix}$ is usually preferred over the $\operatorname{cis}$ notation.

Euler’s formula establishes the fundamental relationship between trigonometric functions and exponential functions. Geometrically, it can be thought of as a way of bridging two representations of the same unit complex number in the complex plane.

Let’s take a look at some of the key values of Euler’s formula, and see how they correspond to points in the trigonometric/unit circle:

- For $x=0$, we have $e^{0} = \cos 0+ i \sin 0$, which gives $1 = 1$. So far so good: we know that an angle of $0$ on the trigonometric circle is $1$ on the real axis, and this is what we get here.

- For $x=1$, we have $e^{i}=\cos 1 + i \sin 1$. This result suggests that $e^i$ is precisely the point on the unit circle whose angle is 1 radian.

- For $x = \frac{\pi}{2}$, we have $e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}} = \cos \frac{\pi}{2} + i \sin \frac{\pi}{2} = i$. This result is useful in some calculations related to physics.

- For $x = \pi$, we have $e^{i\pi} = \cos \pi + i \sin \pi $, which means that $e^{i\pi} = -1$. This result is equivalent to the famous Euler’s identity.

- For $x = 2\pi$, we have $e^{i (2\pi)} = \cos 2\pi + i \sin 2\pi$, which means that $e^{i (2\pi)} = 1$, same as with $x = 0$.

A key to understanding Euler’s formula lies in rewriting the formula as follows: \[ (e^i)^x = \cos x + i \sin x \] where:

- The right-hand expression can be thought of as the unit complex number with angle $x$.

- The left-hand expression can be thought of as the 1-radian unit complex number raised to $x$.

And since raising a unit complex number to a power can be thought of as repeated multiplications (i.e., adding up angles in this case), Euler’s formula can be construed as two different ways of running around the unit circle to arrive at the same point.

Derivations

Euler’s formula can be established in at least three ways. The first derivation is based on power series, where the exponential, sine and cosine functions are expanded as power series to conclude that the formula indeed holds.

The second derivation of Euler’s formula is based on calculus, in which both sides of the equation are treated as functions and differentiated accordingly. This then leads to the identification of a common property — one which can be exploited to show that both functions are indeed equal.

Yet another derivation of Euler’s formula involves the use of polar coordinates in the complex plane, through which the values of $r$ and $\theta$ are subsequently found. In fact, you might be able to guess what these values are — just by looking at the formula itself!

Derivation 1: Power Series

One of the most intuitive derivations of Euler’s formula involves the use of power series. It consists in expanding the power series of exponential, sine and cosine — to finally conclude that the equality holds.

As a caveat, this approach assumes that the power series expansions of $\sin z$, $\cos z$, and $e^z$ are absolutely convergent everywhere (e.g., that they hold for all complex numbers $z$). However, it also has the advantage of showing that Euler’s formula holds for all complex numbers $z$ as well.

For a complex variable $z$, the power series expansion of $e^z$ is \[ e^z = 1 + \frac{z}{1!} + \frac{z^2}{2!} + \frac{z^3}{3!} + \frac{z^4}{4!} + \cdots \] Now, let us take $z$ to be $ix$ (where $x$ is an arbitrary complex number). As $z$ gets raised to increasing powers, $i$ also gets raised to increasing powers. The first eight powers of $i$ look like this: \begin{align*} i^0 & = 1 & i^4 & = i^2 \cdot i^2 = 1 \\ i^1 & = i & i^5 & = i \cdot i^4 = i \\ i^2 & = -1 \quad \text{(by the definition of $i$)} & i^6 & = i \cdot i^5 = -1 \\ i^3 & = i \cdot i^2 = -i & i^7 & = i \cdot i^6 = -i \end{align*} (notice the cyclicality of the powers of $i$: $1$, $i$, $-1$, $-i$. We’ll be using these powers shortly.)

With $z = ix$, the expansion of $e^z$ becomes: \[ e^{ix} = 1 + ix + \frac{(ix)^2}{2!} + \frac{(ix)^3}{3!} + \frac{(ix)^4}{4!} + \cdots \] Extracting the powers of $i$, we get: \[ e^{ix} = 1 + ix-\frac{x^2}{2!}-\frac{i x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} + \frac{i x^5}{5!}-\frac{x^6}{6!}-\frac{i x^7}{7!} + \frac{x^8}{8!} + \cdots \] And since the power series expansion of $e^z$ is absolutely convergent, we can rearrange its terms without altering its value. Grouping the real and imaginary terms together then yields: \[ e^{ix} = \left( 1-\frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!}-\frac{x^6}{6!} + \frac{x^8}{8!}-\cdots \right) + i \left( x-\frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!}-\frac{x^7}{7!} + \cdots \right) \] Now, let’s take a detour and look at the power series of sine and cosine. The power series of $\cos{x}$ is \[ \cos x = 1-\frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!}-\frac{x^6}{6!} + \frac{x^8}{8!}-\cdots \] And for $\sin{x}$, it is \[ \sin x = x-\frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!}-\frac{x^7}{7!} + \cdots \] In other words, the last equation we had is precisely \[ e^{ix} = \cos x + i \sin x \] which is the statement of Euler’s formula that we were looking for.

Derivation 2: Calculus

Another neat way to establish Euler’s formula is to consider both $e^{ix}$ and $\cos x + i \sin x$ as functions of $x$, before differentiating them to find some common property about them.

For that to happen though, one must assume that the functions $e^z$, $\cos x$ and $\sin x$ are defined and differentiable for all real numbers $x$ and complex numbers $z$. By assuming that these functions are differentiable for all complex numbers, it is also possible to show that Euler’s formula holds for all complex numbers as well.

First, let $f_1(x)$ and $f_2(x)$ be $e^{ix}$ and $\cos x + i \sin x$, respectively. Differentiating $f_1$ via chain rule then yields: \[ f_{1}'(x) = i e^{ix} = i f_1(x) \] Similarly, differentiating $f_2$ also yields: \[ f_{2}'(x) = -\sin x + i \cos x = i f_2(x) \] In other words, both functions satisfy the differential equation $f'(x) = i f(x)$. Now, consider the function $\frac{f_1}{f_2}$, which is well-defined for all $x$ (since $f_2(x) = \cos x + i\sin x$ corresponds to points on the unit circle, which are never zero). With that settled, using the quotient rule on this function then yields: \begin{align*} \left(\frac{f_{1}}{f_2}\right)'(x) & = \frac{f_1’(x) f_2(x)-f_1(x) f_2’(x)}{[f_2(x)]^2} \\ & = \frac{i f_1(x) f_2(x)-f_1(x) i f_2(x)}{[f_2(x)]^2} \\ & = 0 \end{align*} And since the derivative here is $0$, this implies that the function $\frac{f_1}{f_2}$ must have been a constant to begin with. What is the value of this constant? Let’s figure it out by plugging in $x=0$ into the function: \[ \left(\frac{f_1}{f_2}\right)(0) = \frac{e^{i0}}{\cos 0 + i \sin 0} = 1 \] In other words, we must have that for all $x$: \[ \left(\frac{f_1}{f_2}\right)(x) = \frac{e^{ix}}{\cos x + i \sin x} = 1 \] which, after moving $\cos x + i \sin x$ to the right, becomes the famous formula we’ve been looking for.

Derivation 3: Polar Coordinates

Yet another ingenious proof of Euler’s formula involves treating exponentials as numbers, or more specifically, as complex numbers under polar coordinates.

Indeed, we already know that all non-zero complex numbers can be expressed in polar coordinates in a unique way. In particular, any number of the form $e^{ix}$ (with real $x$), which is non-zero, can be expressed as: \[ e^{ix} = r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta) \] where $\theta$ is its principal angle from the positive real axis (with, say, $0 \le \theta < 2 \pi$), and $r$ is its radius (with $r>0$). We make no assumption about the values of $r$ and $\theta$, except the fact that they are functions of $x$ (which may or may not contain $x$ as variable). They will be determined in the course of the proof.

(However, what we do know is that when $x=0$, the left-hand side is $1$, which implies that $r$ and $\theta$ satisfy the initial conditions of $r(0)=1$ and $\theta(0)=0$, respectively.)

For what it’s worth, we’ll begin by differentiating both sides of the equation. By the definition of exponential, differentiating the left side of the equation with respect to $x$ yields $i e^{ix}$. After differentiating the right side of the equation, the equation then becomes: \[ i e^{ix} = \frac{dr}{dx}(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta) + r(- \sin \theta + i \cos \theta) \frac{d \theta}{dx} \] We’re looking for an expression that is uniquely in terms of $r$ and $\theta$. To get rid of $e^{ix}$, we substitute back $r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta)$ for $e^{ix}$ to get: \[ i r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta) = (\cos \theta + i \sin \theta) \frac{dr}{dx} + r(- \sin \theta + i \cos \theta) \frac{d \theta}{dx} \] Once there, distributing the $i$ on the left-hand side then yields: \[ r(i \cos \theta-\sin \theta) = (\cos \theta + i \sin \theta) \frac{dr}{dx} + r(- \sin \theta + i \cos \theta) \frac{d \theta}{dx} \] Equating the imaginary and real parts, respectively, we get: \[ ir\cos \theta = i \sin \theta \frac{dr}{dx} + i r\cos \theta \frac{d \theta}{dx} \] and \[ -r \sin \theta = \cos \theta \frac{dr}{dx}-r\sin \theta \frac{d \theta}{dx} \] What we have here is a system of two equations and two unknowns, where $dr/dx$ and $d\theta/dx$ are the variables. We can solve it in a few steps. First, by assigning $\alpha$ to $dr/dx$ and $\beta$ to $d\theta/dx$, we get: \begin{align} r \cos \theta & = (\sin \theta) \alpha + (r \cos \theta) \beta \tag{I} \\ -r \sin \theta & = (\cos \theta) \alpha-(r \sin \theta) \beta \tag{II} \end{align} Second, by multiplying (I) by $\cos \theta$ and (II) by $\sin \theta$, we get: \begin{align} r \cos^2 \theta & = (\sin \theta \cos \theta) \alpha + (r \cos^2 \theta) \beta \tag{III}\\ -r \sin^2 \theta & = (\sin \theta \cos \theta) \alpha-(r \sin^2 \theta) \beta \tag{IV} \end{align} The purpose of these operations is to eliminate $\alpha$ by doing (III) – (IV), and when we do that, we get: \[ r(\cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta) = r(\cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta) \beta \] Since $\cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta = 1$, a simpler equation emerges: \[ r = r \beta \] And since $r > 0$ for all $x$, this implies that $\beta$ — which we had set to be $d\theta/dx$ — is equal to $1$.

Once there, substituting this result back into (I) and (II) and doing some cancelling, we get: \begin{align*} 0 & = (\sin \theta) \alpha \\ 0 & = (\cos \theta) \alpha \end{align*} which implies that $\alpha$ — which we have set to be $\frac{dr}{dx}$ — must be equal to $0$.

From the fact that $dr/dx = 0$, we can deduce that $r$ must be a constant. Similarly, from the fact that $d \theta /dx = 1$, we can deduce that $\theta = x + C$ for some constant $C$.

However, since $r$ satisfies the initial condition $r(0)=1$, we must have that $r=1$. Similarly, because $\theta$ satisfies the initial condition $\theta(0)=0$, we must have that $C=0$. That is, $\theta = x$.

With $r$ and $\theta$ now identified, we can then plug them into the original equation and get: \begin{align*} e^{ix} & = r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta) \\ & = \cos x + i \sin x \end{align*} which, as expected, is exactly the statement of Euler’s formula for real numbers $x$.

Applications

Being one of the most important equations in mathematics, Euler’s formula certainly has its fair share of interesting applications in different topics. These include, among others:

- The famous Euler’s identity

- The exponential form of complex numbers

- Alternate definitions of trigonometric and hyperbolic functions

- Generalization of exponential and logarithmic functions to complex numbers

- Alternate proofs of de Moivre’s theorem and trigonometric additive identities

Euler’s Identity

Euler’s identity is often considered to be the most beautiful equation in mathematics. It is written as

$e^{i \pi} + 1 = 0$

where it showcases five of the most important constants in mathematics. These are:

- The additive identity $0$

- The unity $1$

- The Pi constant $\pi$ (ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter)

- The base of natural logarithm $e$

- The imaginary unit $i$

Among these, three types of numbers are represented: integers, irrational numbers and imaginary numbers. Three of the basic mathematical operations are also represented: addition, multiplication and exponentiation.

We obtain Euler’s identity by starting with Euler’s formula \[ e^{ix} = \cos x + i \sin x \] and by setting $x = \pi$ and sending the subsequent $-1$ to the left-hand side. The intermediate form \[ e^{i \pi} = -1 \] is common in the context of trigonometric unit circle in the complex plane: it corresponds to the point on the unit circle whose angle with respect to the positive real axis is $\pi$.

Complex Numbers in Exponential Form

At this point, we already know that a complex number $z$ can be expressed in Cartesian coordinates as $x + iy$, where $x$ and $y$ are respectively the real part and the imaginary part of $z$.

Indeed, the same complex number can also be expressed in polar coordinates as $r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta)$, where $r$ is the magnitude of its distance to the origin, and $\theta$ is its angle with respect to the positive real axis.

But it does not end there: thanks to Euler’s formula, every complex number can now be expressed as a complex exponential as follows:

$z = r(\cos \theta + i \sin \theta) = r e^{i \theta}$

where $r$ and $\theta$ are the same numbers as before.

To go from $(x, y)$ to $(r, \theta)$, we use the formulas \begin{align*} r & = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2} \\[4px] \theta & = \operatorname{atan2}(y, x) \end{align*} (where $\operatorname{atan2}(y, x)$ is the two-argument arctangent function with $\operatorname{atan2}(y, x) = \arctan (\frac{y}{x})$ whenever $x>0$.)

Conversely, to go from $(r, \theta)$ to $(x, y)$, we use the formulas: \begin{align*} x & = r \cos \theta \\[4px] y & = r \sin \theta \end{align*} The exponential form of complex numbers also makes multiplying complex numbers much easier — much like the same way rectangular coordinates make addition easier. For example, given two complex numbers $z_1 = r_1 e^{i \theta_1}$ and $z_2 = r_2 e^{i \theta_2}$, we can now multiply them together as follows: \begin{align*} z_1 z_2 & = r_1 e^{i \theta_1} \cdot r_2 e^{i \theta_2} \\ & = r_1 r_2 e^{i(\theta_1 + \theta_2)} \end{align*} In the same spirit, we can also divide the same two numbers as follows: \begin{align*} \frac{z1}{z2} & = \frac{r_1 e^{i \theta_1}}{r_2 e^{i \theta_2}} \\ & = \frac{r_1}{r_2} e^{i (\theta_{1}-\theta_2)} \end{align*}

Note

To be sure, these do presuppose properties of exponent such as $e^{z_1+z_2}=e^{z_1} e^{z_2}$ and $e^{-z_1} = \frac{1}{e^{z_1}}$, which for example can be established by expanding the power series of $e^{z_1}$, $e^{-z_1}$ and $e^{z_2}$.

Had we used the rectangular $x + iy$ notation instead, the same division would have required multiplying by the complex conjugate in the numerator and denominator. With the polar coordinates, the situation would have been the same (save perhaps worse).

If anything, the exponential form sure makes it easier to see that multiplying two complex numbers is really the same as multiplying magnitudes and adding angles, and that dividing two complex numbers is really the same as dividing magnitudes and subtracting angles.

Alternate Definitions of Key Functions

Euler’s formula can also be used to provide alternate definitions to key functions such as the complex exponential function, trigonometric functions such as sine, cosine and tangent, and their hyperbolic counterparts. It can also be used to establish the relationship between some of these functions as well.

Complex Exponential Function

To begin, recall that Euler’s formula states that \[ e^{ix} = \cos x + i \sin x \] If the formula is assumed to hold for real $x$ only, then the exponential function is only defined up to the imaginary numbers. However, we can also expand the exponential function to include all complex numbers — by following a very simple trick:

$e^{z} = e^{x+iy} \, (= e^x e^{iy}) \overset{df}{=} e^x (\cos y + i \sin y)$

Note

Here, we are not necessarily assuming that the additive property for exponents holds (which it does), but that the first and the last expression are equal.

In other words, the exponential of the complex number $x+iy$ is simply the complex number whose magnitude is $e^x$ and whose angle is $y$. Interestingly, this means that complex exponential essentially maps vertical lines to circles. Here’s an animation to illustrate the point:

Trigonometric Functions

Apart from extending the domain of exponential function, we can also use Euler’s formula to derive a similar equation for the opposite angle $-x$: \[ e^{-ix} = \cos x-i \sin x \] This equation, along with Euler’s formula itself, constitute a system of equations from which we can isolate both the sine and cosine functions.

For example, by subtracting the $e^{-ix}$ equation from the $e^{ix}$ equation, the cosines cancel out and after dividing by $2i$, we get the complex exponential form of the sine function:

$\sin x = \dfrac{e^{ix}-e^{-ix}}{2i}$

Similarly, by adding the two equations together, the sines cancel out and after dividing by $2$, we get the complex exponential form of the cosine function:

$\cos x = \dfrac{e^{ix} + e^{-ix}}{2}$

To be sure, here’s a video illustrating the same derivations in more detail.

On the other hand, the tangent function is defined to be $\frac{\sin x}{\cos x}$, so in terms of complex exponentials, it becomes:

$\tan x = \dfrac{e^{ix}-e^{-ix}}{i(e^{ix} + e^{-ix})}$

If Euler’s formula is proven to hold for all complex numbers (as we did in the proof via power series), then the same would be true for these three formulas as well. Their presence allows us to switch freely between trigonometric functions and complex exponentials, which is a big plus when it comes to calculating derivatives and integrals.

Hyperbolic Functions

In addition to trigonometric functions, hyperbolic functions are yet another class of functions that can be defined in terms of complex exponentials. In fact, it’s through this connection we can identify a hyperbolic function with its trigonometric counterpart.

For example, by starting with complex sine and complex cosine and plugging in $iz$ (and making use of the facts that $i^2 = -1$ and $1/i = -i$), we have: \begin{align*} \sin iz & = \frac{e^{i(iz)}-e^{-i(iz)}}{2i} \\ & = \frac{e^{-z}-e^{z}}{2i} \\ & = i \left(\frac{e^z-e^{-z}}{2}\right) \\ & = i \sinh z \end{align*} \begin{align*} \cos iz & = \frac{e^{i(iz)}+e^{-i(iz)}}{2} \\ & = \frac{e^z + e^{-z}}{2} \\ & = \cosh z \end{align*} From these, we can also plug in $iz$ into complex tangent and get: \[ \tan (iz) = \frac{\sin iz}{\cos iz} = \frac{i \sinh z}{\cosh z} = i \tanh z \] In short, this means that we can now define hyperbolic functions in terms of trigonometric functions as follows:

\begin{align*} \sinh z & = \frac{\sin iz}{i} \\[4px] \cosh z & = \cos iz \\[4px] \tanh z & = \frac{\tan iz}{i} \end{align*}

But then, these are not the only functions we can provide new definitions to. In fact, the complex logarithm and the general complex exponential are two other classes of functions we can define — as a result of Euler’s formula.

Complex Logarithm and General Complex Exponential

The logarithm of a complex number behaves in a peculiar manner when compared to the logarithm of a real number. More specifically, it has an infinite number of values instead of one.

To see how, we start with the definition of logarithmic function as the inverse of exponential function. That is: \begin{align*} e^{\ln z} & = z & \ln (e^z) & = z \end{align*} Furthermore, we also know that for any pair of complex numbers $z_1$ and $z_2$, the additive property for exponents holds: \[ e^{z_1} e^{z_2} = e^{z_1+z_2} \] Thus, when a non-zero complex number is expressed as an exponential, we have that: \[ z = |z| e^{i\phi} = e^{\ln |z|} e^{i\phi} = e^{\ln |z| + i\phi} \] where $|z|$ is the magnitude of $z$ and $\phi$ is the angle of $z$ from the positive real axis. And since logarithm is simply the exponent of a number when it’s raised to $e$, the following definition is in order: \[ \ln z = \ln |z| + i\phi \] At first, this seems like a robust way of defining the complex logarithm. However, a second look reveals that the logarithm defined this way can assume an infinite number of values — due to the fact that $\phi$ can also be chosen to be any other number of the form $\phi + 2\pi k$ (where $k$ is an integer).

For example, we’ve seen from earlier that $e^{0}=1$ and $e^{2\pi i}=1$. This means one could define the logarithm of $1$ to be both $0$ and $2\pi i$ — or any number of the form $2\pi ki$ for that matter (where $k$ is an integer).

To solve this conundrum, two separate approaches are usually used. The first approach is to simply consider the complex logarithm as a multi-valued function. That is, a function that maps each input to a set of values. One way to achieve this is to define $\ln z$ as follows: \[ \{\ln |z| + i(\phi + 2\pi k) \} \] where $-\pi < \phi \le \pi$ and $k$ is an integer. Here, the clause $-\pi < \phi \le \pi$ has the effect of restricting the angle of $z$ to only one candidate. Because of that, the $\phi$ defined this way is usually called the principal angle of $z$.

The second approach, which is arguably more elegant, is to simply define the complex logarithm of $z$ so that $\phi$ is the principal angle of $z$. With that understanding, the original definition then becomes well-defined:

$\ln z = \ln |z| + i\phi$

For example, under this new rule, we would have that $\ln 1 = 0$ and $\ln i = \ln \left( e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}} \right) = i\frac{\pi}{2}$. No longer are we stuck with the problem of periodicity of angles!

However, with the restriction that $-\pi < \phi \le \pi$, the range of complex logarithm is now reduced to the rectangular region $-\pi < y \le \pi$ (i.e., the principal branch). And if we want to preserve the inverse relationship between logarithm and exponential, we’d also need to do the same to the domain of exponential function as well.

But then, because the complex logarithm is now well-defined, we can also define many other things based on it without running into ambiguity. One such example would be the general complex exponential (with a non-zero base $a$), which can be defined as follows:

$a^z = e^{\ln (a^z)} \overset{df}{=} e^{z \ln a}$

Note

Here, we are not assuming that the power rule for logarithm holds (because it doesn’t), but that the first and the last expression are equal.

For example, using the general complex exponential as defined above, we can now get a sense of what $i^i$ actually means: \begin{align*} i^i & = e^{i \ln i} \\ & = e^{i \frac{\pi}{2}i} \\ & = e^{-\frac{\pi}{2}} \\ & \approx 0.208 \end{align*}

Alternate Proofs of De Moivre’s Theorem and Trigonometric Additive Identities

The theorem known as de Moivre’s theorem states that

$(\cos x + i \sin x)^n = \cos nx + i \sin nx$

where $x$ is a real number and $n$ is an integer. By default, this can be shown to be true by induction (through the use of some trigonometric identities), but with the help of Euler’s formula, a much simpler proof now exists.

To begin, recall that the multiplicative property for exponents states that \[ (e^z)^k = e^{zk} \] While this property is generally not true for complex numbers, it does hold in the special case where $k$ is an integer. Indeed, it’s not hard to see that in this case, the mathematics essentially boils down to repeated applications of the additive property for exponents.

And with that settled, we can then easily derive de Moivre’s theorem as follows: \[ (\cos x + i \sin x)^n = {(e^{ix})}^n = e^{i nx} = \cos nx + i \sin nx \] In practice, this theorem is commonly used to find the roots of a complex number, and to obtain closed-form expressions for $\sin nx$ and $\cos nx$. It does so by reducing functions raised to high powers to simple trigonometric functions — so that calculations can be done with ease.

In fact, de Moivre’s theorem is not the only theorem whose proof can be simplified as a result of Euler’s formula. Other identities, such as the additive identities for $\sin (x+y)$ and $\cos (x+y)$, also benefit from that effect as well.

Indeed, we already know that for all real $x$ and $y$: \begin{align*} \cos (x+y) + i \sin (x+y) & = e^{i(x+y)} \\ & = e^{ix} \cdot e^{iy} \\ & = ( \cos x + i \sin x ) (\cos y + i \sin y) \\ & = (\cos x \cos y-\sin x \sin y) \\[1px] & \; \; + i(\sin x \cos y + \cos x \sin y) \end{align*} Once there, equating the real and imaginary parts on both sides then yields the famed identities we were looking for:

\begin{align*} \cos (x+y) & = \cos x \cos y-\sin x \sin y \\[4px] \sin (x+y) & = \sin x \cos y + \cos x \sin y \end{align*}

Conclusion

As can be seen above, Euler’s formula is a rare gem in the realm of mathematics. It establishes the fundamental relationship between exponential and trigonometric functions, and paves the way for much development in the world of complex numbers, complex functions and related theory.

Indeed, whether it’s Euler’s identity or complex logarithm, Euler’s formula seems to leave no stone unturned whenever expressions such $\sin$, $i$ and $e$ are involved. It’s a powerful tool whose mastery can be tremendously rewarding, and for that reason is a rightful candidate of “the most remarkable formula in mathematics”.

| Description | Statement |

|---|---|

| Euler’s formula | $e^{ix} = \cos x + i \sin x$ |

| Euler’s identity | $e^{i \pi} + 1 = 0$ |

| Complex number (exponential form) | $z = r e^{i \theta}$ |

| Complex exponential | $e^{x+iy} = e^x (\cos y + i \sin y)$ |

| Sine (exponential form) | $\sin x = \dfrac{e^{ix}-e^{-ix}}{2i}$ |

| Cosine (exponential form) | $\cos x = \dfrac{e^{ix} + e^{-ix}}{2}$ |

| Tangent (exponential form) | $\tan x = \dfrac{e^{ix}-e^{-ix}}{i(e^{ix} + e^{-ix})}$ |

| Hyperbolic sine (exponential form) | $\sinh z = \dfrac{\sin iz}{i}$ |

| Hyperbolic cosine (exponential form) | $\cosh z = \cos iz$ |

| Hyperbolic tangent (exponential form) | $\tanh z = \dfrac{\tan iz}{i}$ |

| Complex logarithm | $\ln z = \ln |z| + i\phi$ |

| General complex exponential | $a^z = e^{z \ln a}$ |

| De Moivre’s theorem | $(\cos x + i \sin x)^n = \cos nx + i \sin nx$ |

| Additive identity of sine | $\sin (x+y) = \sin x \cos y + \cos x \sin y$ |

| Additive identity of cosine | $\cos (x+y) = \cos x \cos y-\sin x \sin y$ |

Prefer the PDF version instead?

Get our complete, 22-page guide on Euler’s formula—in offline, printable PDF format.

Dear madam, can we get the pdf copy of the same ?

It is very effective post and make our students to grasp the concept very easily.

With regards.

Mr. M ANAND

Associate Professor in Mathematics

Department of Humanities & Sciences

MALLA REDDY INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY

HYDERABAD-INDIA-500100

Hi Anand. Appreciate the prompt reply. We’ll think about that! In the meantime, you might find the Print function from a browser useful (which allows saving to PDF as well).

Shouldn't right-hand side of the rewritten expression be cos (x) + i sin(x)?

Hi Ruben. Yes it is! This is just to make the point that the cis notation is not as popular as the $e^{ix}$ notation.

Agreed. I would love a PDF of this article, with the links to the Desmos animation and the Khan video written with their URLs.

Thanks for your feedback Beth!

Compact, easy to read and well written. I liked it 🙂

Hi Anon. Glad you liked it!

Wow! The article written is really amazing. I would be glad if the pdf of this article is available to download. I am a student of 12th standard of Aligarh Muslim University.

Hi Rohit. Thanks for the feedback. It’s amazing that you’re reading this while in 12th standard!

Vary well presented. Thank you.

There is typo after the following line (cos and sin are interchanged).

"A key to understanding Euler’s formula lies in rewriting the formula as follows: "

Hi Shyama. Nice catch! The sine/cosine interchange has now been corrected!

Enjoyable

Hi Kirk. Glad you like it!

First of all, thank you very much for this article — it helped me a lot to wrap my head around complex functions and get some intuition about these. I love that you put out multiple Euler's formula derivations and proceeded to introducing other complex functions in a logically continuous manner.

However, I have two remarks:

1. sin(z) and cos(z) definitions are missing. I would like to see some additional proof that the sin(x) formula can be expanded to sin(z) (complex numbers). You jump immediately to sin(iz) while I still cannot see how sin(x) has the same properties as sin(x+iy). It's not like I'm trying to say it's not true — it's just I feel that there is a missing logical link.

2. While introducing general complex exponential, you say "we are not assuming that the power rule for logarithm holds". Okay, but the formula definitely appears to do so, otherwise I have no other explanation. But — you also link to an article, where the issue is also touched upon, however slightly different formula is provided (https://mathvault.ca/logarithm-theory/#Redefining_Exponential_Functions_of_Arbitrary_Bases). A much clearer one. Why not use the same formula here? Then the definition becomes painfully obvious.

Otherwise, it's an excellent article. Thank you.

Hi Bart. Great remark! For your first point, if it seems like that the transition from $\sin x$ to $\sin z$ is missing in the Hyperbolic Functions section, it’d be because in the paragraph preceding the section, we’ve alluded to a sneaky approach through which that is not needed (namely, defining $e^z$, $\sin z$ and $\cos z$ as complex power series, proving Euler’s formula and finally rewriting $\sin z$ and $\cos z$ in terms of complex exponentials). It might not answer the question you have in mind, but it sure does evade the problem!

For your second point, the idea is that we’re simply defining $a^z$ — which didn’t have meaning before — as $e^{z \ln a}$, and citing the power rule for logarithm as our inspiration. In the other article you cited, we used the Power Property for exponent (i.e., $(e^x)^y = e^{xy}$) as our inspiration instead, but keep in mind that even in that case, the situation is not as simple as it seems because the Power Property also doesn’t hold for all complex numbers!

Thanks so much! This will be a great teaching tool!

Thank you Vance. We’re glad that you find it useful!

Thank you for going above and beyond in providing such valuable info on this website. I appreciate the well-structured articles that offer a comprehensive understanding of various subjects.

Hi Islam. Glad you like it!