(For more on matrices, vectors, vector products and other related topics, check out our Linear Algebra Ebook Series.)

Today, Connor asked the following question involving a system of linear equation with an additional parameter:

Given that $x_1 + hx_2 = 4$ and $3x_1 + 6x_2 =8$, find all pairs of the form $(x_1,x_2)$ satisfying both equations.

OK…What do we do with that additional $h$? Well, read on!

Table of Contents

Ignoring the h First

We are given this system of linear equations from the get-go:

\begin{cases}x_1+hx_2=4 & (a) \\ 3x_1+6x_2=8 & (b) \end{cases}

What to do? Well, we can try to solve this system of linear equations by regarding $h$ as an ordinary coefficient first, and see what it takes us to as we proceed judiciously. First, dividing the equation $(b)$ by $3$ on both sides yields the following equivalent system:

\begin{cases}x_1+hx_2=4 & (1) \\ x_1+2x_2=\frac{8}{3} & (2) \end{cases}

Turning the 2nd equation into $(2)-(1)$, we get:

\begin{align*} \begin{cases} x_1+hx_2=4 \\ (2-h)x_2=\frac{8}{3}-4 \end{cases} \qquad & \Leftrightarrow \qquad \begin{cases} x_1+hx_2=4 & (3) \\ (h-2)x_2=4-\frac{8}{3} = \frac{4}{3} & (4) \end{cases} \end{align*}

At this point, our latest system is still equivalent to the original one (i.e., $(a)$ and $(b) \iff (3)$ and $(4)$) . And with $(4)$, we are definitely one step closer towards solving for $x_2$. But before we do just that, notice that we can’t solve for $x_2$ by moving $h-2$ to the right, if $h-2=0$ (i.e., $h=2$). This would then open up two cans of worms…

Case 1 — When h=2

Replace $h$ with 2 in the equations $(3)$ and $(4)$, the following system pops up:

\begin{cases} x_1+2x_2=4 \\ 0= \frac{4}{3} \end{cases}

Oops. Contradiction. That can’t happen at any rate, so there is no solution in this case.

In fact, we don’t even have to get to $(3)$ and $(4)$ to see it. This is because if we just plug in 2 into $h$ by the time we got to $(1)$ and $(2)$, we would get the following system:

\begin{cases} x_1+2x_2=4 \\ x_1+2x_2=\frac{8}{3} \end{cases}

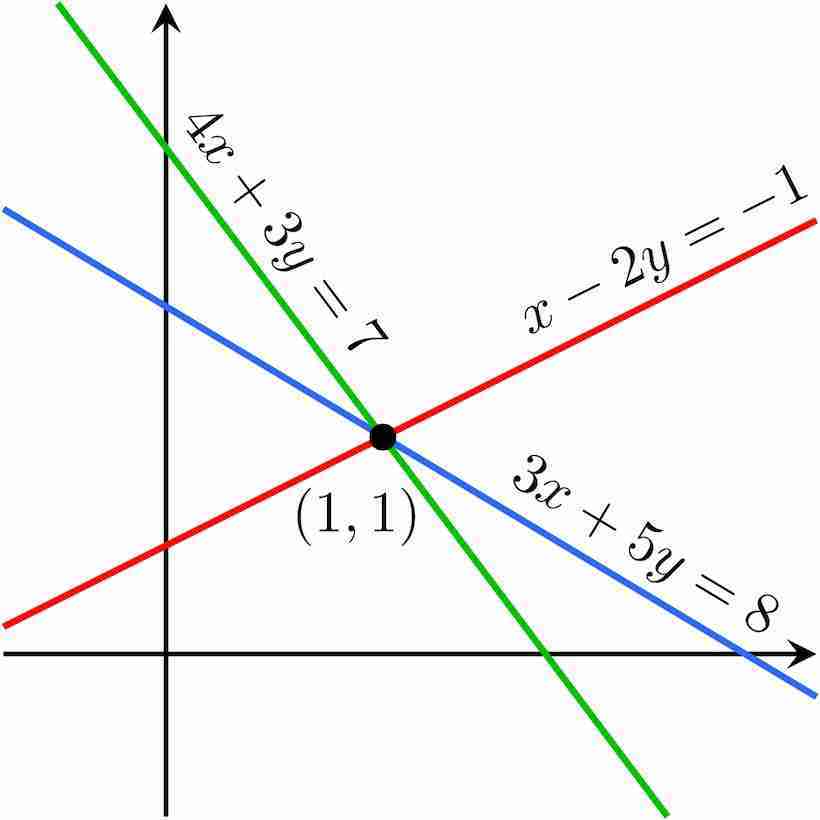

which, as we can see, is already a system whose equations contradict each other. Here — a picture is worth a thousand words:

Case 2 — When h ≠ 2

Once the above trivial hurdle is clear, we can then move on to something more serious. For the record, here is the latest system we have so far:

\begin{cases} x_1+hx_2=4 & (3)\\ (h-2)x_2=4 – \frac{8}{3} = \frac{4}{3} & (4) \end{cases}

Since $h \ne 2$ now, $h-2 \ne 0$. We can therefore proceed to divide the equation $(4)$ by $h-2$ on both sides, in which case we get:

\begin{cases} x_1+hx_2=4 & (5) \\ x_2= \frac{4}{3(h-2)} & (6) \end{cases}

Lastly, if we turn $(5)$ into $(5)-h(6)$, we get a very neat system in return:

\begin{cases} x_1=4 – \frac{4h}{3(h-2)}=\frac{8h-24}{3h-6} & (7) \\ x_2= \frac{4}{3(h-2)}= \frac{4}{3h-6}& (8) \end{cases}

So for each $h \ne 2$, we get a unique pair of solution of the form $\left( \dfrac{8h-24}{3h-6}, \dfrac{4}{3h-6} \right)$.

Some Illustrations

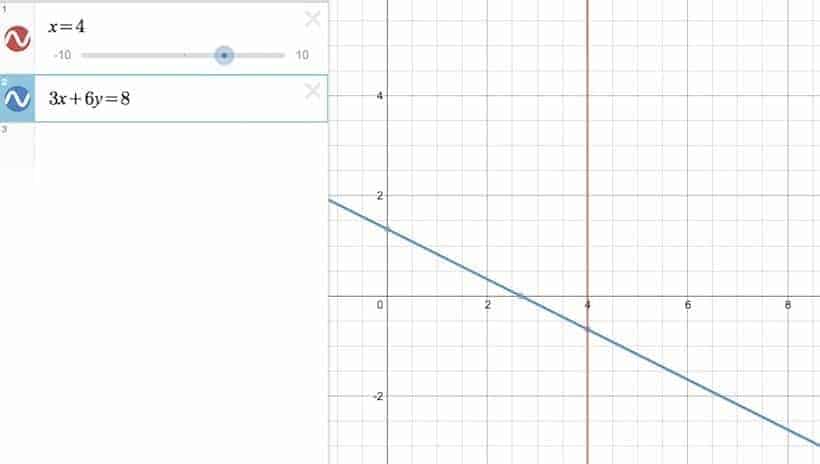

For example, if $h=0$, then the original system becomes:

\begin{cases} x_1=4 \\ 3x_1+6x_2=8 \end{cases}

In which case, the unique solution would be:

$$\left( \frac{8h-24}{3h-6} , \frac{4}{3h-6} \right)_{h=0} = \left( 4,-\frac{2}{3} \right)$$

Here is a picture:

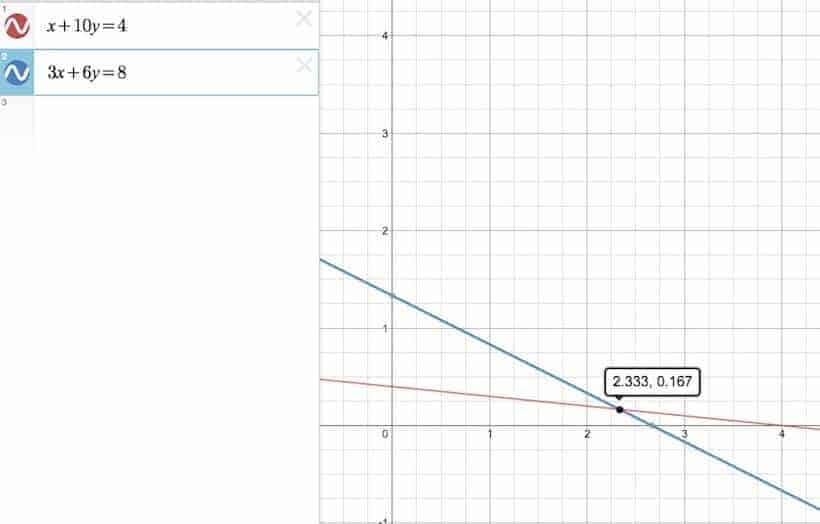

And in the case where $h=10$, the original system becomes:

\begin{cases} x_1+10x_2=4 \\ 3x_1+6x_2=8 \end{cases}

In which case, the unique solution would be:

$$\left(\frac{8h-24}{3h-6}, \frac{4}{3h-6} \right)_{h=10} = \left(\frac{56}{24}, \frac{4}{24} \right) = \left( \frac{7}{3}, \frac{1}{6} \right)$$

Here is a picture again:

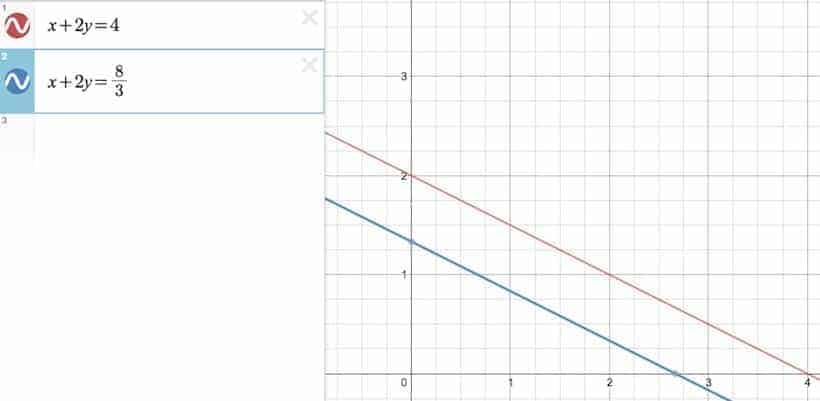

And this, is how we can solving infinitely many system of linear equations all at once! For a last sanity check, here’s a Desmos animation we’ve put together — just so that we can put everything we’ve learned thus far into a single slide.